Age: 78

Sex: female

Date: 10 Nov 1900

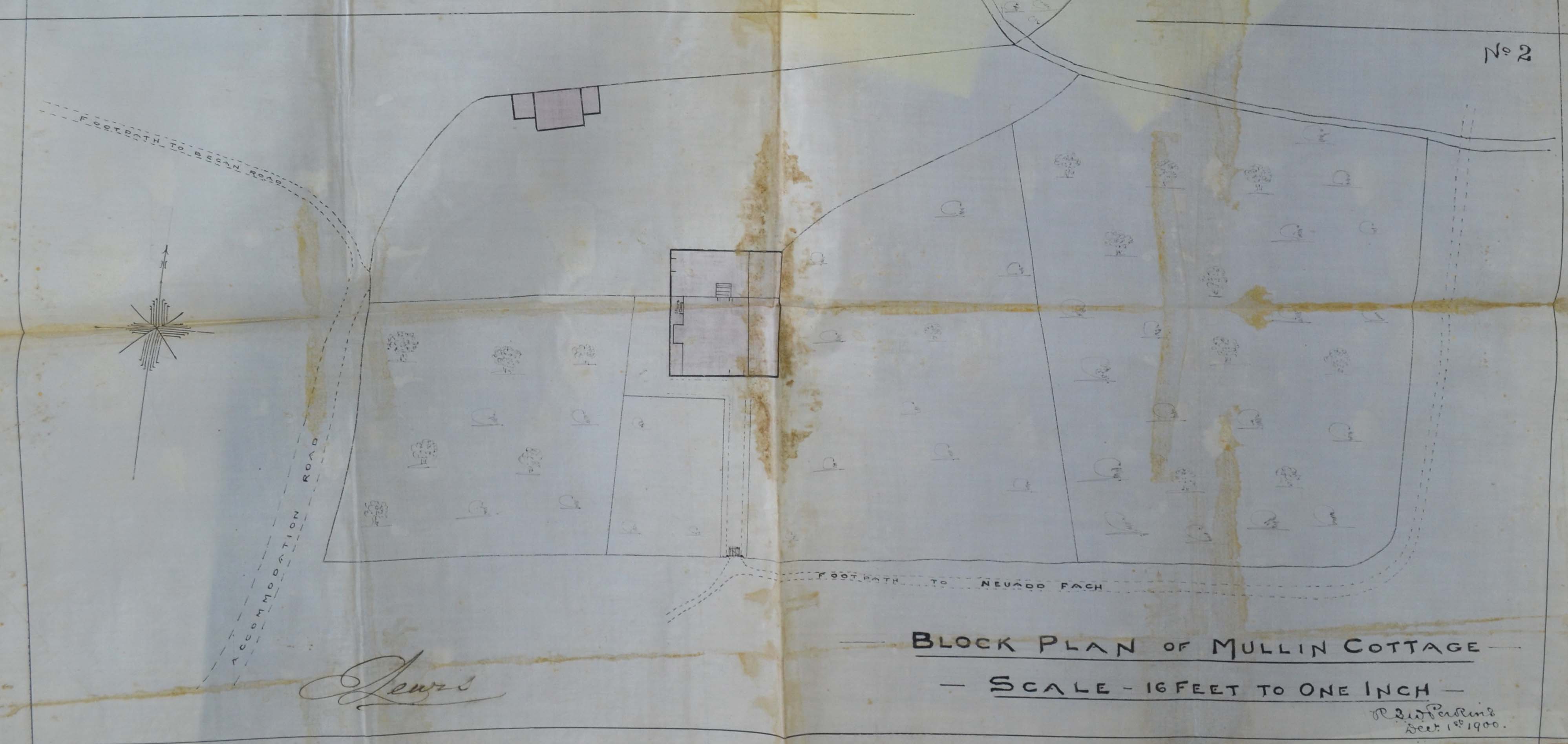

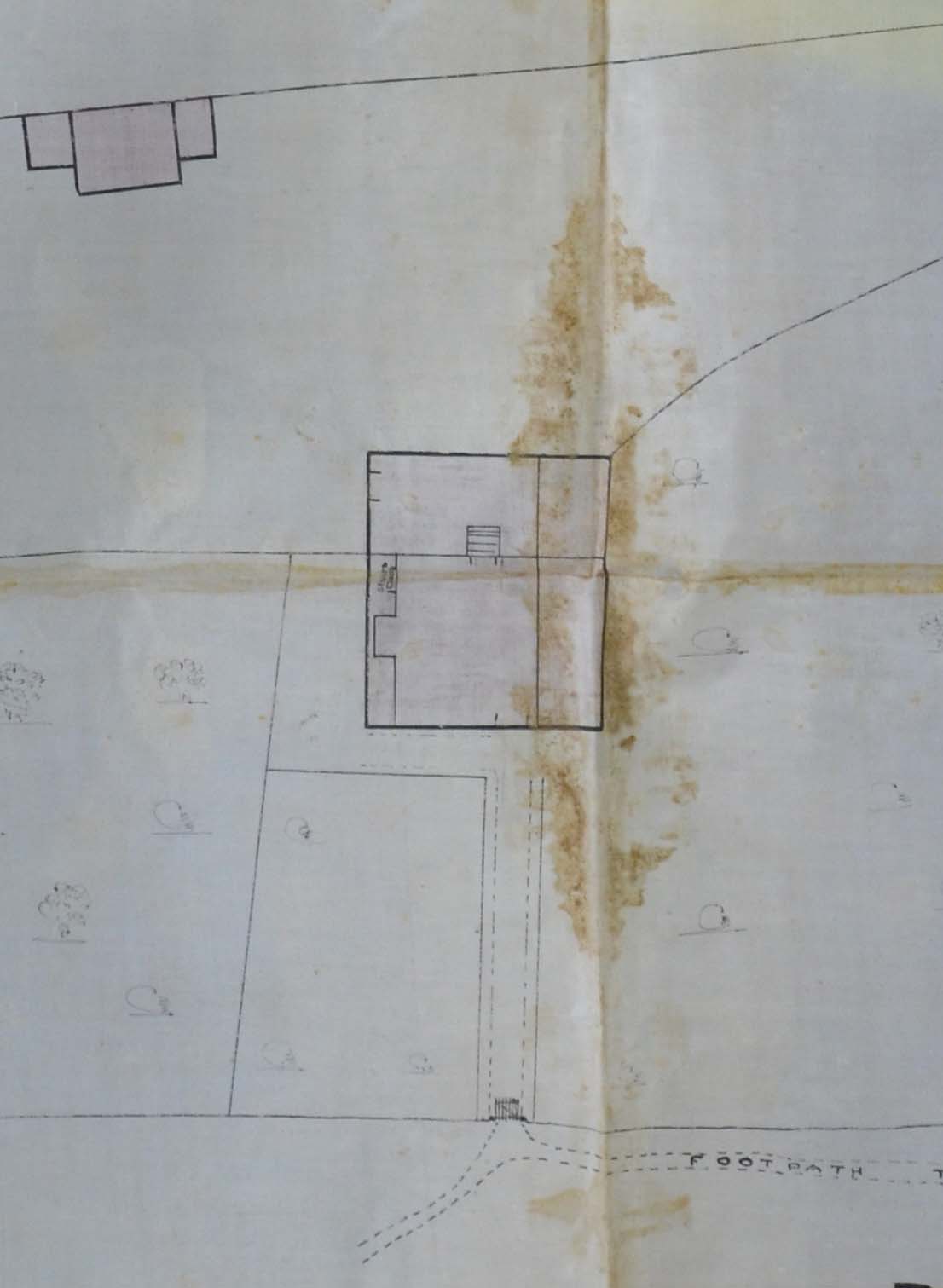

Place: Mullen Cottage, Began Road, St Mellons, Monmouthshire

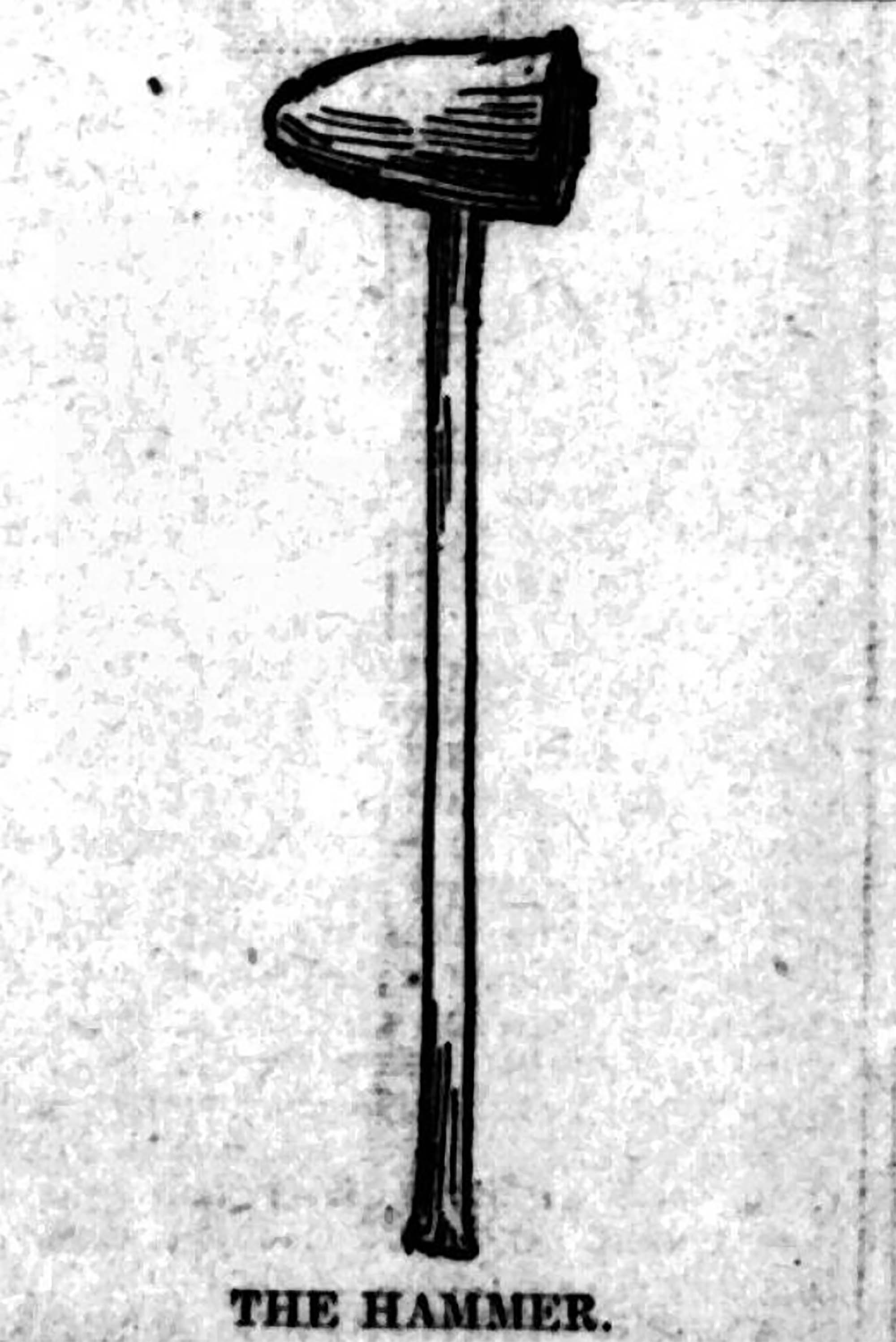

Hannah Williams was beaten to death in her cottage with a coal hammer on 10 November 1900.

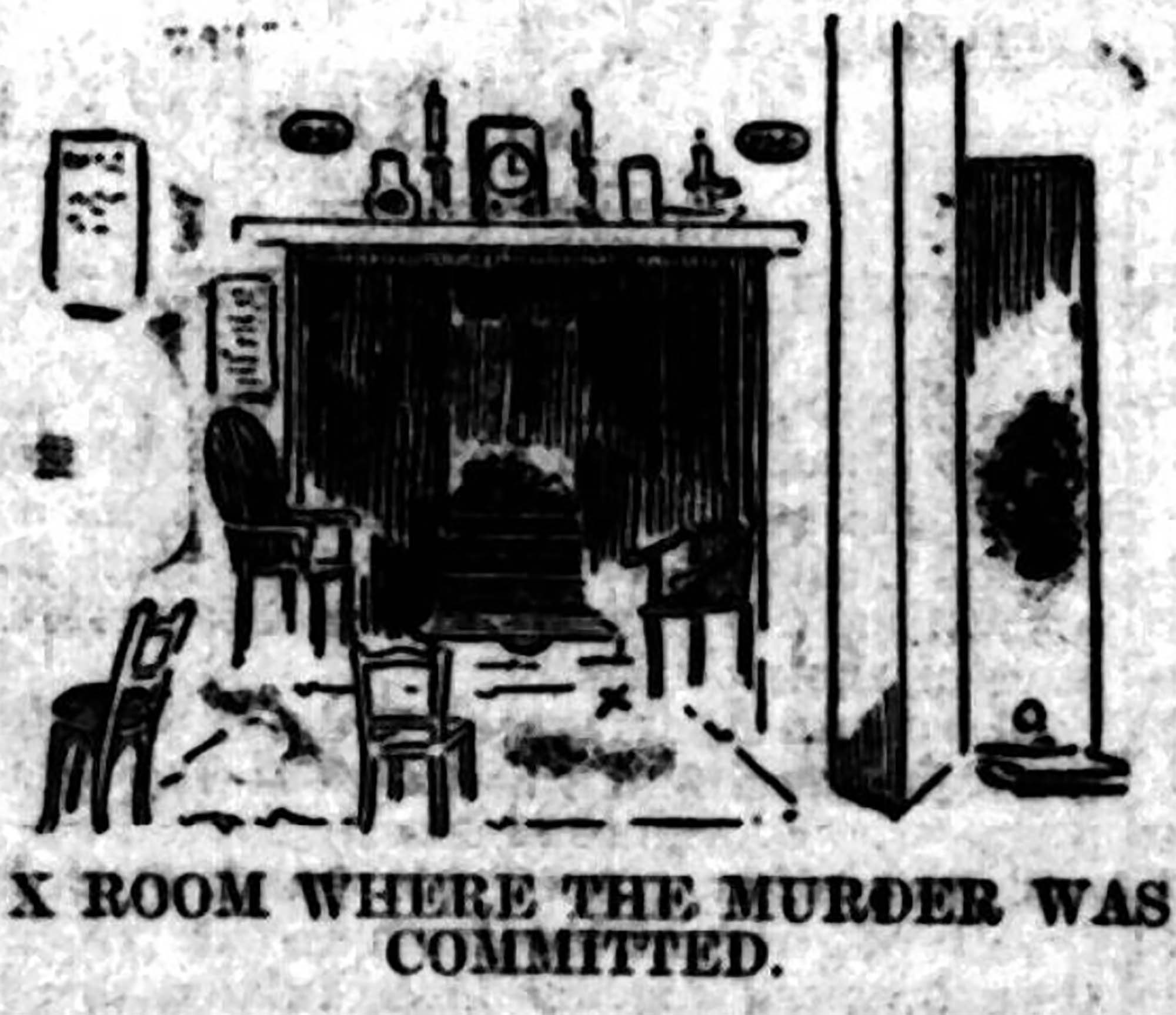

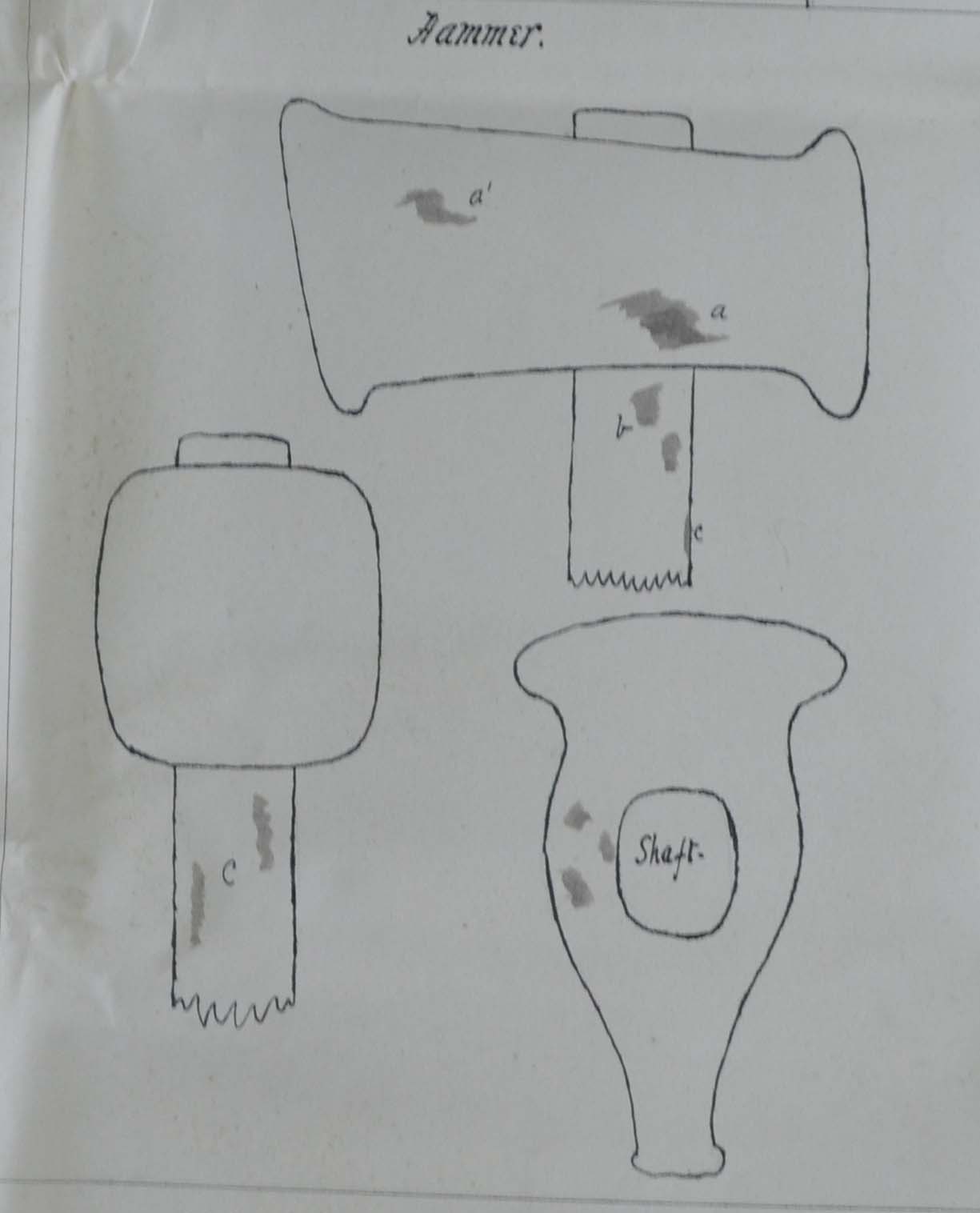

She was beaten to death with a coal hammer that had ordinarily been kept in the kitchen after which her throat was cut.

Police initially directed their investigations to tracing an unknown man who was alleged to have left the district by omnibus and who related an extraordinary story to the driver and had seemed unusually agitated.

However, following Hannah Williams’s funeral, a 29-year-old Labourer was arrested on suspicion of her murder and charged and was tried at the Monmouthshire Assizes on 20 February 1901, but found not guilty.

The Labourer had worked at Pentwyn Colliery as a surface workman and had lived at Cefn Mably Cottages.

Hannah Williams had been the widow of a gardener on a neighbouring estate and had been pensioned by the landowner. She was said to have been frugal in her habits and added to her small income by market gardening and poultry farming.

It was generally believed that she kept her savings in the house and that robbery had been the motive. Her cottage had been ransacked from top to bottom, but it appeared that the killer had got away with only a metal framed watch and chain worth only a few shillings. Police found a considerable sum of money concealed in a box amongst some old rags and over £5 in her pockets.

It was heard that Hannah Williams' life was insured to the sum of 3d a week with the Prudential and that her relatives would be entitled to something like £5.

Mullen Cottage was situated on a piece of rising ground overlooked by Cefn Mably, and was about 150 yards off the parish road, which was known locally as the Began Road, and in order to approach it one had to cross a field and walk along a little bridge, consisting of a single plank, that spanned a deep brook, which at the time was considerably swollen by the rains. The cottage had at some distant point been the humble homestead of a farm, but had since been detached from the Maesycrochan holding, and let separately.

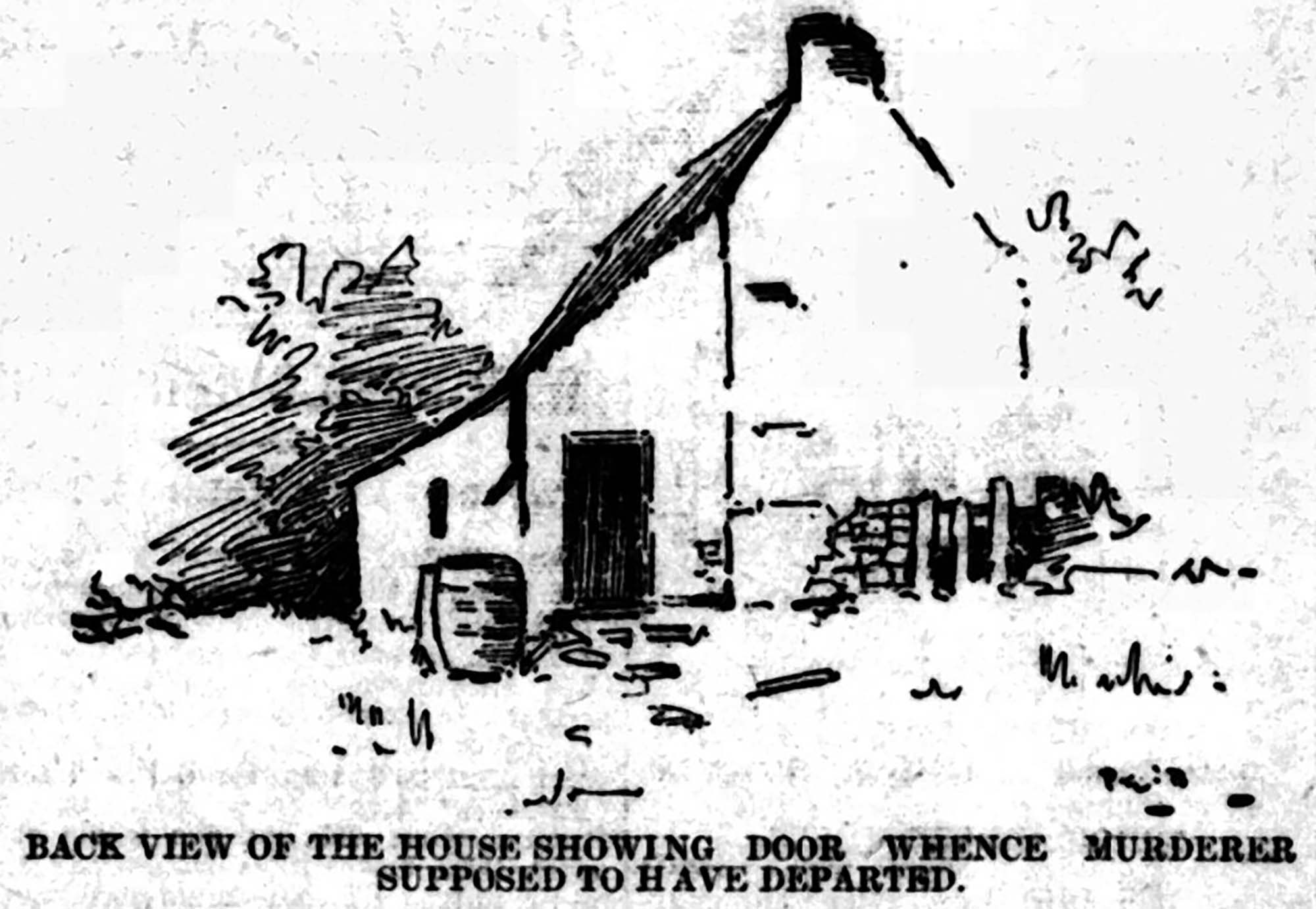

It had been a small thatched house, with two apartments on the ground floor, a sitting room or front kitchen, and a back kitchen, together with a sort of lumber or store place, and two bedrooms above. Outside the front door there had been a path that ran up through the field to another cottage, Neuado Fach, about 300 yards away, occupied by a couple, who were Hannah Williams's nearest neighbours.

Mullen Cottage stood in an enclosure of fences and had been in the midst of about half an acre of orcharding and had additional loneliness added to it by standing close alongside a thickly wooded plantation.

However, Mullen Cottage has since been demolished.

Hannah Williams's mother had lived in Mullen Cottage with Hannah Williams. On the morning of 10 November 1900 she went to Cardiff, as was her wont, on Market Day, leaving Hannah Williams alone in the house.

At about 3pm the same day, the Labourer, who was married to a niece of Hannah Williams and lived about two miles away, visited the cottage and, as he stated, found Hannah Williams lying dead there on the kitchen floor, her head having been smashed and her throat cut.

He then informed some neighbours and then fetched the police.

However, five days later, after attending the funeral, he was arrested.

It was heard that he had made variations in his statements regarding what he had been doing on the morning of the murder, with it being emphasised that he had said that he had not left his cottage on the morning of the murder and had also said that he had later been 'talking to the chaps', but that it was not clear who the chaps were.

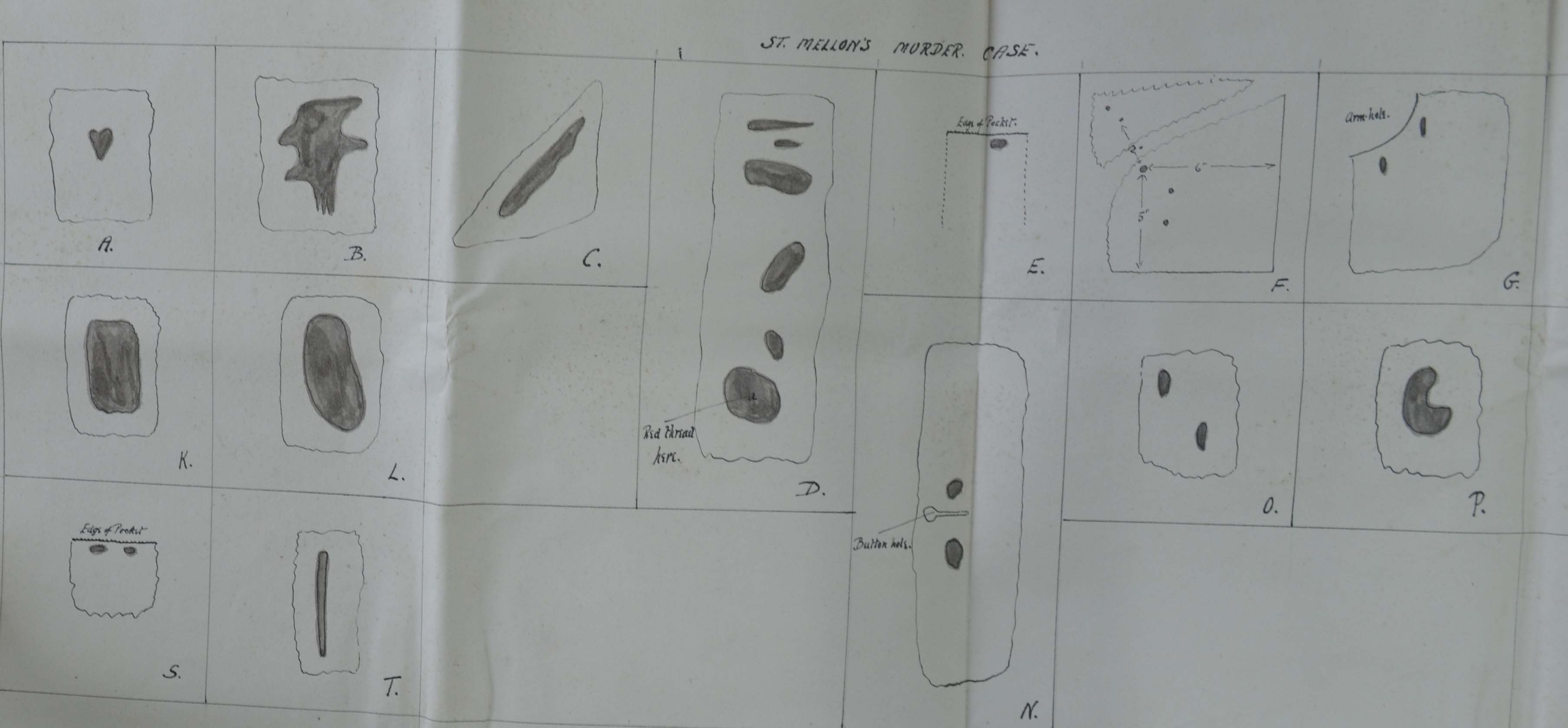

It was also noted that blood and vomit stains were found on his working clothes, and noted that blood and vomit were also found at the scene of the crime. It was further noted that although it could not be determined whether the blood stains had been human, that the scientific analysis of their pattern showed that the stains were on all his garments and splashed in directions contrary to that in which blood from the Labourer's nose, from a nose bleed, would be expected to fall. It was also noted that his clothes had been washed, with considerable effort made to scrub and wash the blood stains away. The prosecution stated that it was significant that every spot of his clothes had been subjected to washing and scrubbing and that it was too much to think that the Labourer himself would have gone to so much trouble to remove from his working clothes every little spot of blood if they had, as he had said, been the result of a nose bleed.

The court then heard from Hannah Williams's daughter who stated that the Labourer had been to the cottage a number of times in the previous week and noted that whilst there he had made efforts to hide himself from the gaze of stray callers and submitted that what he had in fact been doing had been studying the means and safest methods of perpetuating the crime. It was also heard that he had even asked Hannah Williams which way he could leave the cottage without being seen by neighbours that lived on the other side of the wood.

It was also noted that when the Labourer made his first statement to the police that he said that he had gone no further than the kitchen but that when he was left alone he told the constable's wife who was also there that it was a case of murder and that all the rooms had been ransacked, stating that he had gone upstairs and seen.

At the trial it was noted that the witnesses had been given copies of their statements and when it was asked whether it was fair that the witnesses had their memories refreshed the superintendent said that he had just followed the instructions of the solicitor for the Treasury and the judge noted that whilst it was improper, that he didn't blame the officer.

It was also heard that the Labourer had initially said that he had not left his house until 3pm, but his wife later contradicted that, saying that he had gone to work early in the morning, whereupon the Labourer said that he had gone to the pit, but that he didn't work.

The court heard that the Labourer had not worked in the week prior to the murder, and for some reason had spent a good deal of time at Mullen Cottage which was said to have not been usual for him as he was not in the habit of frequenting the house and prior to that week had not been there for some months.

It was heard that he had gone there on Monday 5 November 1900 as early as 7am and had remained there the whole of the day, stating that he had been working the previous night, however, that was later found to be untrue.

He again visited her on Wednesday 7 November 1900 and spent a considerable amount of time there. It was heard additionally that he had attempted to conceal himself when a neighbour called at the cottage on two occasions, staying in another room for the whole time that she was there, with no explanation given for why he did so. The prosecution stated that the reason he hid was because he was endeavouring to find an opportunity to commit the robbery on the Saturday.

The Labourer also visited on the Thursday, 8 November 1900 and asked about some washing that he wanted doing and asked that they not tell that he had been over so early.

It was then heard that on the Saturday morning that he had left home to go to work at 6am, but that he was not going to work and had no reason to have anticipated that there would be work as when he had previously drawn his wages on the Friday before that he had been told to come back on the Monday and as such, he could not have been going to work on the Saturday morning.

The prosecution added that after leaving his house that morning that he neither went to Pentwyn, nor anywhere else and that he was not seen by anybody until the afternoon, adding that whether he had been hiding in the woods behind Mullen Cottage in the forenoon of that day, it was impossible to say.

The prosecution then noted that a dog was heard to bark about 200 yards away from Mullen Cottage about the time that the murder was thought to have occurred.

The Labourer was next seen at his own house, which was a mile and a quarter from Mullen Cottage, at about 2.40pm whilst his wife and step-mother were having a meal. They said that he arrived, walking quickly, and that after having some food, he changed his clothes and then left again at about 3pm. It was heard that he didn't give any explanation for where he had been but had said during the meal that he had been out with the chaps. However, the prosecution stated that they had not been able to determine who the 'chaps' had been.

After then leaving his house he went to Mullen Cottage, and on his way passed the time of day with Hannah Williams's neighbour and another man, walking fast. Then, after ten minutes, he returned and told the men that something terrible had happened at Mullen Cottage and asked them to go with him as the 'old woman' had been murdered.

They then went to the cottage together, it being noted that the Labourer appeared cognisant of the fact that the front door had been locked and they went round to the back door.

They then found Hannah Williams on the floor in the kitchen in a pool of blood and vomit.

The doctor that gave evidence at the trial noted that vomiting was not an unnatural sequence of a heavy blow to the head and that she had been struck repeatedly and that there were possibly convulsive movements of the muscles that had then induced her murderer to cut her throat, noting that her throat was cut after her death.

The court heard that after the discovery of Hannah Williams that the other men suggested that the Labourer should go and inform the police.

It was noted that he had told them that the reason he had gone there was because he was looking for pigs and that the site he found was enough for him and that he had turned back.

However, it was heard that he later told the police constable that he had gone in and felt Hannah Williams's pulse and then left, and that further, whilst the police constable was telegraphing for assistance that the Labourer had told his wife that he had gone upstairs and that the whole house was ransacked and intimated that Hannah Williams had had a bit of money.

The prosecution stated that those were important facts as they showed that the Labourer had both gone upstairs and had known that Hannah Williams had some money.

It was heard that when the doctor was called in at 7pm that he concluded that Hannah Williams had been dead for 5 to 6 hours which would put her time of death as being between 1pm and 2pm, which was about the time that the dog had been heard barking 200 yards away.

The prosecution stated that whether the Labourer heard the dogs or saw the neighbour passing the cottage and made his escape without having completed his search for the money, that it was for the jury to say.

The court heard that it was later found that Hannah Williams had skilfully hidden about £30 amongst some rags which was later found and that she had also had money in a satchel purse on her person which she had been lying on and that although efforts had been made to get to it that, it was still there.

Nothing other than an old watch was missed from the house which was never found.

It was noted that due to the Labourer's bold moves in being the person to find the body and reporting the murder to the police that he was not suspected at first, but that after certain statements he made, the police interviewed him again after the funeral, asking about whether he had been at work and noting that his wife had told them that he had not been at work, with his response then being that he had gone to work, but had not worked.

It was further noted that when asked about the possible blood stains on the clothes he was wearing, that he had said that he had had a nose bleed and had also cut his finger and had gone on to say that a fellow-worker had even seen it. However, when the police questioned the fellow-worker, he told them that he had seen nothing of the kind.

Following that, the Labourer was arrested and his clothes sent away for analysis. The analysis showed that his clothes had blood stains on them, but that they had been thoroughly scrubbed locally, that being that wherever there were traces of blood that the garments had been subjected to vigorous scrubbing, but that they had not been so vigorously scrubbed that science could not find traces of them.

It was further heard that the blue slop that the Labourer had been wearing was stained both with blood and vomit, which was said to have been significant.

It was also noted that the mode in which Hannah Williams was murdered was such that there would not be a vast quantity of blood on account that she was dead at the time her throat was cut and her heart not beating and that as such there would be no spurt of blood which anyone standing near would be certain to have been covered with, and that as a result there would have only been a sprinkling of blood of a spasmodical kind, which was consistent with that found on the Labourer's clothes.

Further, it was noted that the stains found on his clothing were not such as would be expected from a bleeding nose.

The prosecution added that there was no reason why the vigorous scrubbing, as found on his clothing, should have been carried out, but that on the other hand, it was precisely what would have bene expected in the case of a person wishing to remove traces of their guilt.

At the trial it was heard that there had been a suggestion that Hannah Williams might have been murdered by two woodmen that had previously lodged with her about a year earlier, but that the prosecution had traced them and they had come to the trial to give evidence as to prove they had nothing to do with it if required and that although they could not exclude the possibility of some other third party being involved, that they had exhausted all possibilities with regards to finding other people that could have committed the murder.

Hannah Williams's sister said that the Labourer came to the cottage on the Monday, 5 November 1900 at about 7am and was let in by Hannah Williams and stayed all day and that he had been wearing his work clothes. She said that he visited again on the Wednesday, 7 November 1900, and that he was there when she got home from Cardiff and that he told her that he wanted her to get him something from Cardiff. She said that she was there when the neighbour came in and said that the Labourer went up into the bedroom whilst she was there and that after she left had come back down and told her that he didn't wish to see her, but didn't say why.

She said that he came again on the Thursday, 8 November 1900 to ask about her going to his house to wash and asked her not to say that he had been over so early, and that he stayed until 10pm and that when the neighbour visited again that he again went upstairs to avoid her, staying there until she left, noting that she had been there about half-an-hour. She said that when he then came out that he asked her which way he could go home without passing any cottages. However, it was noted at the trial that she had not heard him say that herself, but that Hannah Williams had told her that he had said that and she admitted that she didn't hear it herself.

She said that when the Labourer left the cottage that he went out the back door, which was the door nearer the road.

She said that she next went to Cardiff market on the Saturday at about 9am, at which time Hannah Williams had been 'smart' and had come to see her off at the gate and that she returned about 4.30pm and about a quarter of a mile from the cottage met the Labourer who told her that something shocking had happened at her house and that Hannah Williams was dead.

She noted that the Labourer had then been wearing his best clothes and had 'tidied himself up'.

She said that she then went back to Mullen Cottage and saw Hannah Williams in a chair and the house ransacked. She said that she found the money amongst the rags and also the purse on Hannah Williams and that the only thing that was missing was the watch.

She noted that she had known the Labourer for about four years since he married her first cousin and that she believed that he had been living at Cefn Mably Cottage for two years before that.

After the Labourer went to inform the police constable and was left along with his wife, the police constables wife said that they spoke about the murder and they had the following exchange:

Labourer: The things upstairs were all turned upside down.

Constable's Wife: I thought the old woman was comparatively poor.

Labourer: Oh, she had a bit of money.

However, it was noted that she didn't say anything about that immediately and she said that she didn't place any importance to that or say anything about it to her husband until after the magistrates committal hearing when she heard the other evidence.

The Labourer's mother-in-law said that on the morning of the murder that the Labourer got up at 4.45am and brought her and his wife a cup of tea in bed and then left the house, wearing his working clothes and that he later returned at 2.40pm as they were having a meal and that he joined them.

She said that he then washed and changed his clothes and went out, but that as he was going out she asked him where he had been so long and that he had replied:

She said that earlier in the week that Hannah Williams had been ill and so that as he was leaving she asked him to go over and see how she was.

The defence then asked her some questions:

Defence: Did rabbits and pheasants come to your house?

Mother-in-law: I've seen them there. I was told they were given.

Defence: Never mind, you saw them?

Mother-in-law: Yes.

Defence: And you knew there are poachers in Monmouthshire.

Mother-in-law: Oh yes.

Do you know that there was an entertainment of some sort going on that afternoon in the neighbourhood?

Mother-in-law: I heard about it.

Defence: And it is customary, is it not, for the men on Saturday afternoon to clean and change their clothes?

Mother-in-law: Yes.

Where you friendly with deceased?

Mother-in-law: Oh yes.

Defence: And also prisoner was friendly?

Mother-in-law: Oh yes. The last time the murdered woman was over at our house she chaffed prisoner and asked him if he was too proud to come over to the Mullen to see her sometimes.

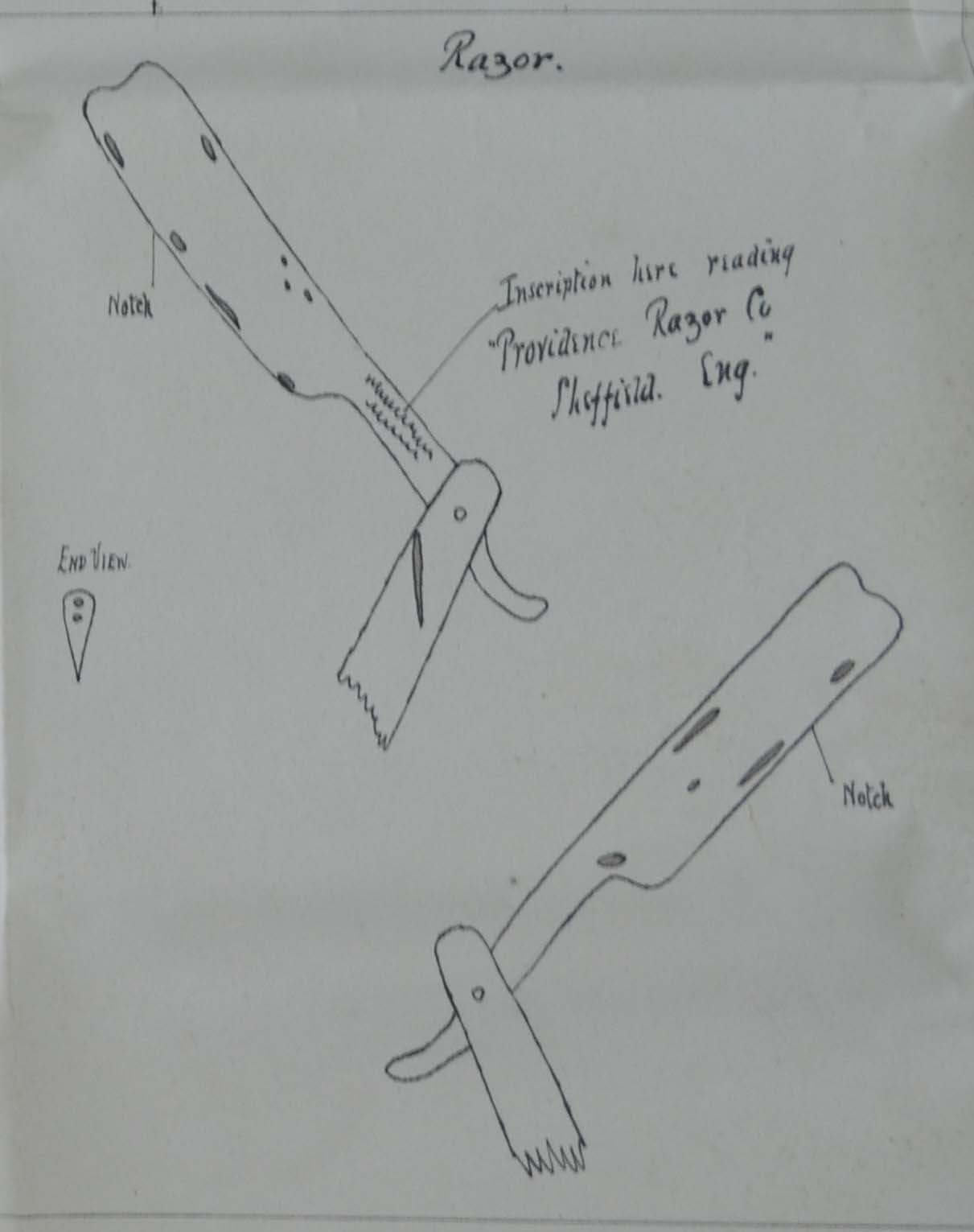

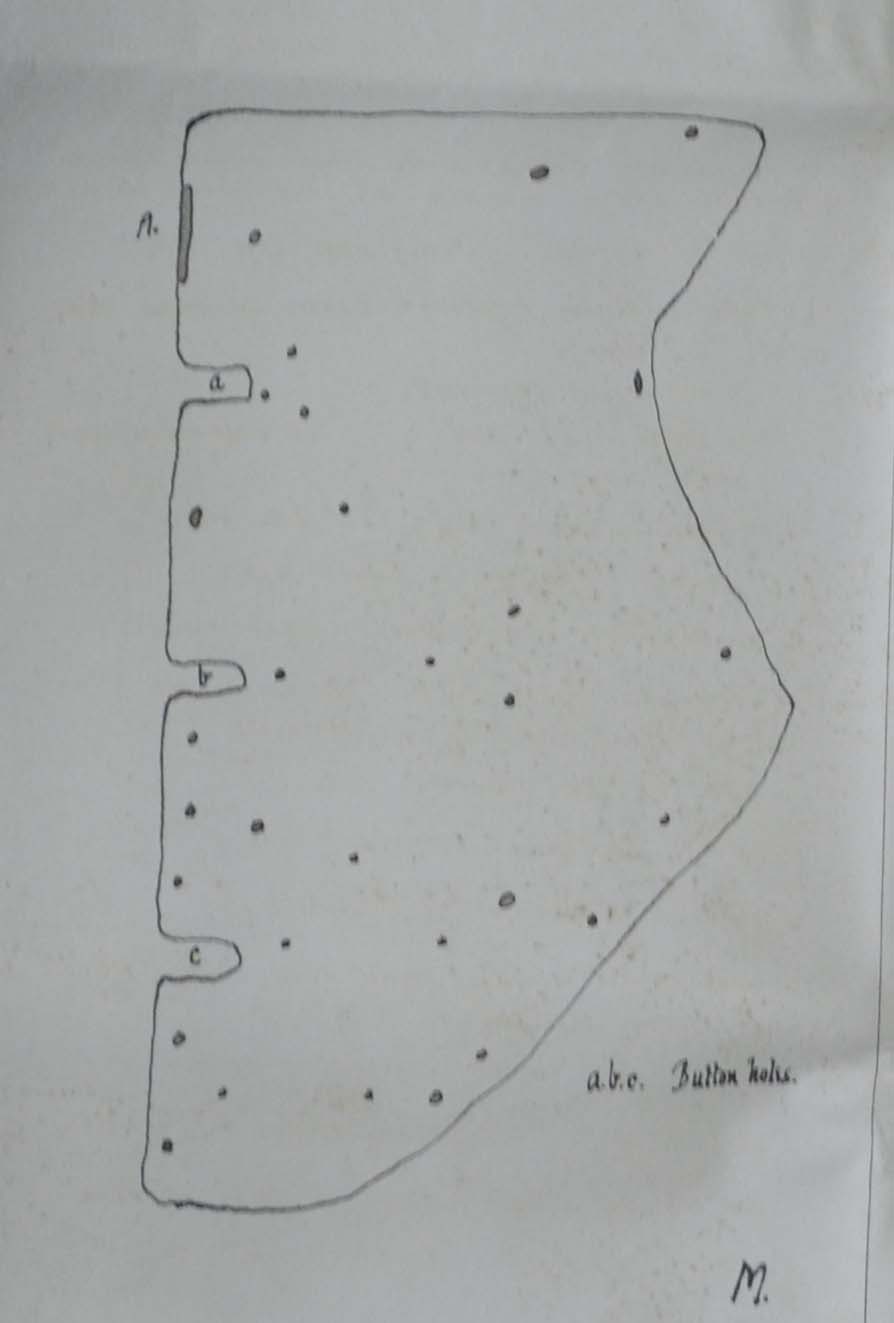

Evidence was also heard relating the various blood stains found on the Labourer's clothing and detailed illustrations were presented in evidence showing their characteristics.

When the prosecution summed up, they said that it was not probable that the person who had gone to rob Hannah Williams had gone to commit murder. He added that the murderer was probably detected in rifling the house and that whoever did it had known the house and that the Labourer was a person that knew the house.

The defence noted that it had been shadowed forth that the Labourer had been out poaching on the morning of the murder, and questioned why if that had been the case that it had not been mentioned earlier as poaching in daylight was a slight and innocent matter.

The prosecution noted that it was curious that whether the bloodstains had been human or otherwise that they were all over his clothing that day, and added that the vomit found on the slop was definitely identified and that it was found to have been mixed with blood that had been deposited at the same time as the vomit.

When the defence summed up they noted that there was nothing against the Labourer other than the highly scientific evidence regarding his clothing and two false statements made by him. He then noted that not a single spot of blood had been however shown to have been of human origin and questioned why the evidence of the blue slop had not been submitted until two weeks before the trial and noted that the jury were not able to see the vomit as there was no microscope in the court.

The defence further noted that the prosecution had also presented a white handkerchief with a speck of blood on it, and asking the jury to examine it, defied them to find the spot of blood.

The defence also noted that it would have been likely that it the Labourer had been the murderer that he would have been very likely to have known where to find the money in the drawer and that in the purse.

When the judge summed up he emphasised the absence of direct evidence connecting the labourer to the crime and the absence of motive and the uncertainty that must be present in the jury's mind regarding the scientific evidence. He stated that circumstances adverse to the Labourer was his discarding of his working clothes and almost immediate washing and scrubbing of them along with the near total absence of an explanation as to where he had been on the morning of the murder.

However, after a short retirement the jury at the Monmouth Assizes on 20 February 1901, found the Labourer not guilty and he was acquitted.

see www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk

see National Archives - ASSI 6/36/11

see Leicester Chronicle - Saturday 17 November 1900

see Dundee Evening Post - Monday 12 November 1900

see Dundee Courier - Monday 12 November 1900

see Lloyd's Weekly Newspaper - Sunday 18 November 1900

see Star of Gwent - Friday 22 February 1901 (pictures)

see Hull Daily Mail - Thursday 21 February 1901

see Weekly Dispatch (London) - Sunday 18 November 1900 (pictures)

see Western Daily Press - Thursday 21 February 1901

see Western Mail - Wednesday 14 November 1900 (pictires)

see Royal Cornwall Gazette - Thursday 22 November 1900

see Unsolved 1900