Age: 56

Sex: male

Date: 17 May 1938

Place: Quays Farm, Risby, Suffolk

William Murfitt died from cyanide poisoning.

It was found that someone had put cyanide in a tin of Fynnon Salts that he would take each morning, a few hours before he had drunk them.

There was a prime suspect, a 40-year-old woman that lived as a housekeeper at a nearby farm, but it was concluded that there was not enough evidence to charge her or anyone else with his murder.

It was thought that he had died from either cyanide potassium or cyanide sodium poisoning, which bore a close similarity. The doctor said that cyanide potassium and cyanide sodium were of the same colour and appearance of Fynnon Salts and that it was very volatile. He said that because the body normally contained a little potassium and sodium, it was impossible to differentiate between the two on deciding which one had caused his death.

The doctor that examined his body said that William Murfitt had been a healthy but fat man and had a large liver as well as a large heart, which was said to have been in good condition. The doctor said that he considered that a dose of approximately 10 grains of cyanide had caused his death, noting that the recognised fatal dose was 5 grains.

The doctor said that the effect of taking such a poison was that the person simply sank to the ground in a state of collapse, became unconscious, and died within 15 minutes. He noted, that William Murfitt had taken an unusually long time, nearly an hour, to die after taking the fatal dose.

When the police from Scotland Yard arrived, they found William Murfitt lying on a camping bed fully dressed, the only people there being a neighbour and a brother-in-law. They were then told that the doctor had come and taken away the tin of salts before they had arrived.

When the police went into the drawing room they saw William Murfitt's wife and the neighbour’s wife. They said that William Murfitt's wife was crying and seemed very upset and kept saying, 'I wish I had taken a dose as well'. They said that she was at times hysterical.

The police then searched William Murfitt's clothing but found nothing material and arranged for him to be taken to the West Suffolk General Hospital.

When the police examined the dining-room they noted that it had been cleared, with the exception of three glass tumblers and a spoon, one of which contained some clear liquid. The spoon was also found to be powdery. The items were later taken away as evidence and the house was fully searched.

The tin of Fynnon Salts, tumblers, spoon and nine receptacles containing human organs from the post-mortem were then all sent to London for analysis on 17 May 1938 along with three other jars of human organs on 19 May 1938.

The inquest into his death was opened on 18 May 1938, but then adjourned for a later date to be fixed.

When the police looked into William Murfitt's background they found that he had married on 13 July 1903. They had two sons, one of whom, aged 21, had been away at sea at the time of the murder on the SS Baron Murray on which he was an engineer, the other son, aged 34, was a director of Messrs. Percy Mears Ltd, motor agents, at 218 Great Portland Street, W1.

William Murfitt himself lived at Quays Farm with his wife, a female secretary, and two maids. He was a well-known farmer and had taken over Quays Farm, which comprised of a farm-house and 1,000 acres of arable and pasture-land 5 1/2 years earlier. He also rented two other farms with an approximate aggregate acreage of 350 at Heath Farm in Risby and West Farm in Ickburgh, Norfolk.

It was said that he had farmed on scientific and mechanised lines and had employed about 80 men who were said to have held him in high esteem so much so that his death was lamented by his employees and residents in general in the area, who felt that his passing would lower the wage-earning capacity of the district as he had paid good wages and would afford employment to those who were willing to work.

It was noted that his prospects and goods were undoubtedly good, and that although he was not wealthy, he was certainly solvent. It was noted that his net profits for the year ending May 1937 were £3,491 and that for the year ending May 1938 were between £5,000 and £6,000. It was noted that a statement of affairs drawn up by a Wisbech firm of accountants on 9 May 1938 with the object of obtaining an overdraft from the National Provincial Bank in Bury St Edmunds for the purpose of a business expansion showed an estimated surplus of £11,484.

It was noted that there had been the suggestion advanced in some directions that William Murfitt was in financial difficulties and had been refused further credit by his two banks, the Midlands Bank in Kings Lynn and Barclays in Chatteris and that as a consequence he had sought the overdraft with the Bury St Edmunds branch of the National Provincial Bank, but had been refused and that that had driven him to commit suicide. However, the police report stated that despite the fact that his financial figures ridiculed that suggestion, when the police approached the manager of the National Provincial Bank, they were informed that William Murfitt had approached them on 13 May 1938 intimating that he wanted to change his bank and desired an overdraft, and that the matter had been referred to head office and that the decision was still pending when William Murfitt was murdered, but were also told that the question of a refusal had never arisen.

It was found that William Murfitt had suffered from a mild form of diabetes for a number of years and had been under the care of a diabetic specialist. It was noted that the state of his organs revealed that he had been a heavy drinker at one time, although he was known to have been a teetotaller for some years. He was also a non-smoker. It was heard that he had periodically visited his family doctor because he was under the impression that he had been suffering from blood pressure.

It was heard that William Murfitt had been concerned for his health as he had been rejected by a number of assurance companies as an undesirable subject and had been unable to effect a contract on his life with any one of them. It was noted that he had on occasions referred to his state of health and had not anticipated a long life.

However, it was noted that despite his pessimism regarding his health, he had generally been seen as an active and efficient business man and was fond of society and sport and had been a member of several clubs in Newmarket, and had been a syndicate member the previous winter which had rented a shoot in the district.

It was found that generally speaking, practically every one that knew him had described him as a man who was fond of life and certainly not the type of man that would commit suicide.

It was noted that after his death, on 10 June 1938, a sale of his machinery, cattle, and personal effects took place at the farm, which realised more than they were put in for at valuation. It was noted then that about £1,600 of William Murfitt's liabilities comprised of a loan to him by his wife and that her personal estate was in the region of £5,000 and that she had guaranteed her husband's overdrafts to the extent of about £4,000.

His will, which was dated 3 February 1937, showed that he had left all his personal chattels to his wife and that she was also to receive the income from the residue of the estate, placed upon Trust, during her lifetime, and that after her death it was to be divided in equal shares between his two sons.

The police report noted that William Murfitt was undoubtedly a man of loose morals and that throughout his married life he had been intimate with other women, including his servants.

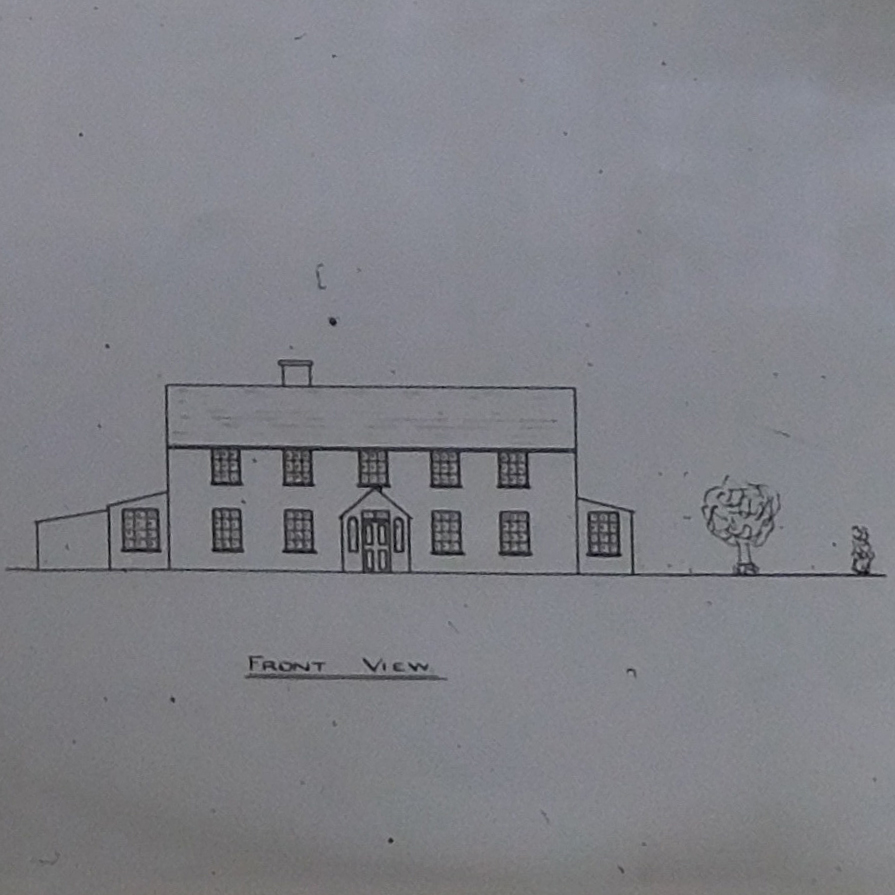

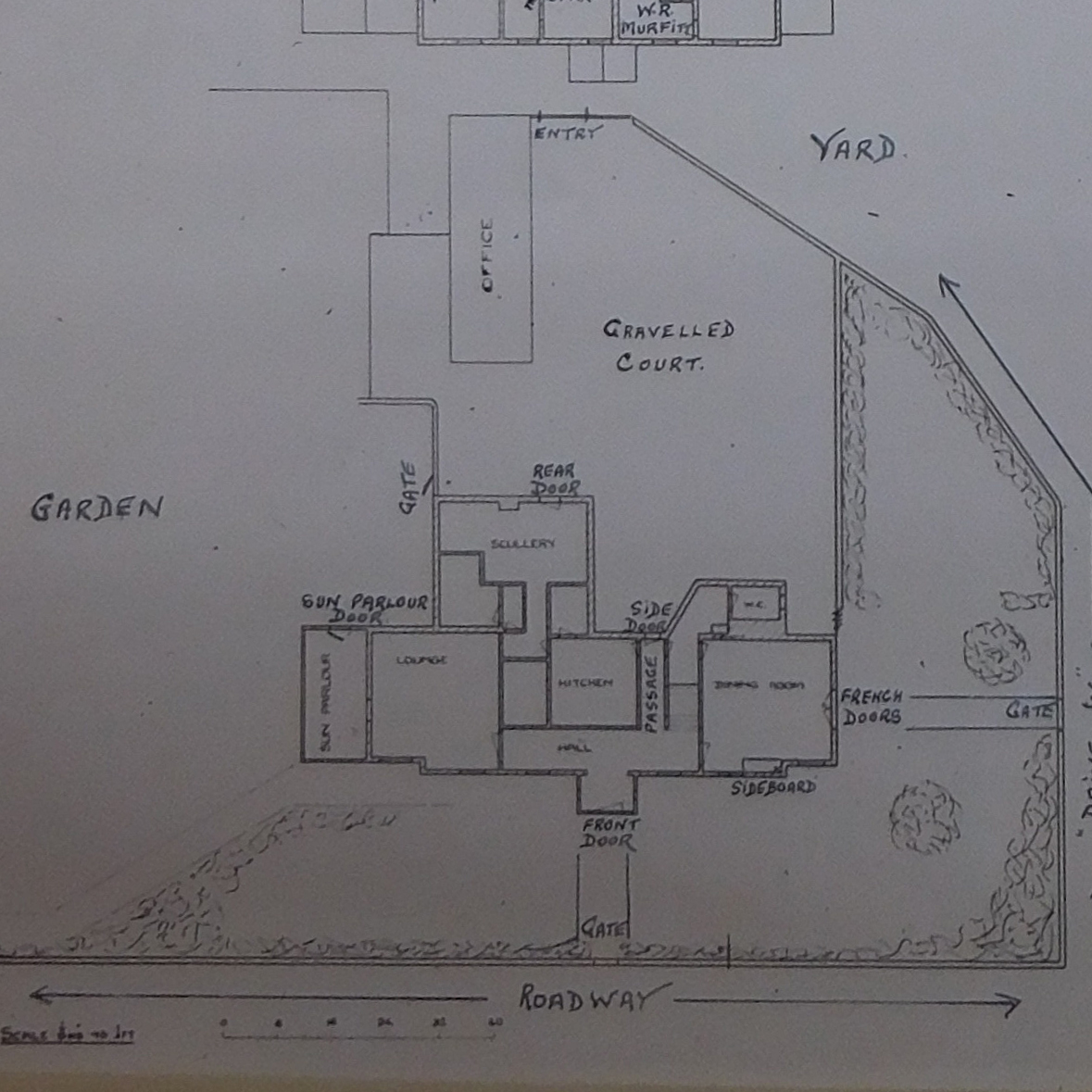

Quays Farm house was situated about ten yards from a secondary thoroughfare that ran through Risby, a village of about 200 people, and which was little used except by local residents.

The farm-house was adjacent to the usual farm buildings and at the rear there was a brick building that was used by William Murfitt as an office. The house itself comprised of 13 rooms and a bathroom and was practically surrounded by a low wall, shrubs and trees. On entering the grounds from the front, one would scarcely be seen from the farm buildings, but when entering from the back one would easily be observed from the farm-yard. There were four doors to the house, one at the front and three at the rear. The front door was fitted with a Kenrick lock, which was of a Yale type, to which there were four keys, one of which was found to be missing. The front door also had a box lock which was not used beyond just turning the handle to open the door. Of the three doors to the back of the house, one into the sun-parlour was fitted with a Willen lock, which was also of a Yale pattern, and which was almost invariably bolted from the inside and rarely used. The other two doors gave access to the kitchen and passage respectively and were fitted with large box locks, the only keys to which were left in the locks on the inside of the doors, and as such could not consequently be operated with a false key.

The farm-house itself was served with two flights of stairs, one leading from the hall and used principally by members of the family and the other leading up from the kitchen in the back up the house. Next to the front stairway that adjoined the dining room there was a passage that led from the hall to one of the doors at the rear of the house which was generally referred to as the 'side door'.

The dining room was noted as being fitted with two doors, one leading immediately into the hall and the other into the rear of the passage adjacent to the 'side door'. The dining room was also fitted with French doors, but they were never opened.

The sideboard on which the tin of Fynnon Salts was usually kept with a tantalus and bottles of wines and spirits, stood just inside the hall door of the dining room. It was marked on the building plan on the sideboard in the dining room with a cross.

When the layout of the upstairs was detailed, which was also shown in plan form, it was noted that the secretary occupied the room above the dining room, and that the door of her room was immediately at the top of the front stairway. The bedroom of William Murfitt and his wife was then at the opposite end of the house and overlooked the roadway. The bedroom that was normally used by the son that was away at sea was next to the secretaries and was unoccupied around the time of the murder. Next to the son's room there were three small unoccupied bedrooms and opposite them was an office that William Murfitt reserved for his private use. There was also a bathroom and a lavatory near to the secretary’s room.

There was a third floor to the farm-house in which the two maids shared a bedroom that looked out on to the yard at the rear of the house. There was also a large room on the third floor in which disused correspondence and stationery was kept. A short flight of stairs then led up to the attic where fishing tackle and other miscellaneous articles were deposited.

It was noted that William Murfitt was known to have gone into the attic on the morning of his murder to get a length of rope, but it was stated that that was accounted for and had no bearing on the investigation.

There was a 'drive-in' from the roadway, which ran along the side of the house into the yard at the rear. Then, at the back of the house, there was a large gravelled court through which people passed from the yard to get to the house. The farm fields lay beyond the yard and there was a large garden for the family’s private use on the opposite side of the 'drive-in'.

The sanitation at the farm was modernistic, but co-operative with a large cesspool that was situated about 30 yards from the house behind some farm outbuildings. The cesspool was within a few feet of the roadway and very close to another entrance to the farm that was used principally for cattle and agricultural vehicles. It was noted that that entrance was immediately opposite Hall Lane and that access to Quays Farm-house could be gained there by a short circuitous route that would bring a person into the yard at the rear of the house.

When the police interviewed William Murfitt's wife, they found out that he was in the habit of rising each morning at about 6.30am and after partaking in a cup of tea, which was made by one of the maids at about 7am he would attend to the business connected with the farm and would then later return to the house for breakfast at about 8am. However, they said that she also told them that William Murfitt would occasionally get up at 5.30am, but that after following the same normal routine, would return for breakfast at the usual hour.

It was also learnt that for many years, William Murfitt and his wife had been in the habit of taking Kruschen Salts in bed with their early morning cups of tea and that the jars containing the salts were mostly kept in their bedroom, but at odd times would be in the dining room, either in the sideboard or on top of it. However, it was also learnt that they had latterly introduced Fynnon Salts into the house which William Murfitt would regularly take at the breakfast table each morning immediately before his meal.

William Murfitt's wife said that she was unable to recollect when the Fynnon Salts were first used in the house, but agreed that she had made her first purchase of them from Leesons, the chemist at 31 Abbeygate Street in Bury St Edmunds on 9 March 1938, and said that she would always fetch the tins of salts from the chemist herself together with other sundries. However, she asserted that William Murfitt had brought at least one tin of Fynnon Salts into the house prior to her initial purchase.

When the police went to see Leesons at 31 Abbeygate Street they said that they could only trace three purchases of Fynnon Salts by William Murfitt's wife, viz on 9 March 1938, 4 April 1938 and 30 April 1938. It was heard that the sales had been credited to William Murfitt's account as William Murfitt's wife didn't make cash purchases at the shop. Enquiries were also made at Boots the chemist, which William Murfitt's wife said she also used, but no purchases could be traced there.

William Murfitt's wife said that each tin would normally last about a month and that the first tin would be finished up before a second was purchased. She added that she would dispose of the empty tin and would not have emptied the remainder from an old tin into a new tin, and said neither would anyone else in the house.

It was heard that William Murfitt had apparently got up at about 5.30am on 17 May 1938, although William Murfitt's wife said that she wasn’t altogether definite about that as she said that she had been half asleep. She said that she got up at about 8am and that it was about that time that William Murfitt came into the house for his breakfast. She said that when he did so, she and the secretary were sitting at the table having breakfast. She said that just prior to William Murfitt entering the room, she had taken two tumblers and the tin of Fynnon Salts from the sideboard and noted that she recollected that the tin of salts was not in its usual position and had been standing on the right side of the sideboard, although she noted that sometimes that was so. She said that she removed the lid of the tin and noticed that the salts seemed a little damp and on the top were a brownish colour. She said that the colour was not particularly marked, but very similar to a shade of brown sugar that was shown.

She said that she remarked to the secretary, 'Do you think there's anything the matter with these salts?,' but said that she didn't remember whether the secretary examined them. She said that she removed the brownish particles with a teaspoon by tilting the tin and pushing them into a slop basin that was on the table, noting that in the process of doing that she removed some of the white particles as well, and altogether removed quite a teaspoonful.

William Murfitt's wife said that she didn't take any salts herself that morning saying that she 'Just didn't fancy taking them', although said that in the first place she had intended doing so.

She said that as William Murfitt came in she took a teaspoonful of salts from the tin and placed them in a tumbler and then added some hot water from the water jug use for the tea and then handed them to him. She said that William Murfitt then drank them and said, 'They taste nasty. Did you give me too much?' and said that she replied, 'No, the usual dose'. She noted that she didn't think that she drew to his attention the fact that the salts had been damp and discoloured before he took them.

William Murfitt's wife said that she then took the paper bag containing the salts from the tin and put them in the oven to dry because they seemed a little damp.

William Murfitt's wife said that about five minutes after he had taken the salts he got up and said, 'I do feel ill. Get a doctor', and then immediately collapsed on to the floor.

William Murfitt's wife said that the doctor was then telephoned for by the secretary and two farm hands then came in to support William Murfitt on the floor with cushions.

William Murfitt's wife said that she had no idea that William Murfitt was dying and so she ordered the maids to clear the table so that the room would be tidy when the doctor came. As such, in the process of that, the slop basin into which the brown substance had been deposited was taken away and washed. William Murfitt's wife later said that she could not be certain whether the tumbler taken by the police later was the one that had contained the salts or not.

When the doctor arrived at the house, he asked William Murfitt 's wife whether William Murfitt had taken his breakfast, and she told him that he had only taken his salts. The doctor then requested that she get them from the oven and she caused one of the maids to do so. The doctor then smelt the salts and advised William Murfitt's wife not to smell them, but she did so and said that they smelt like ammonia. The doctor then took possession of the salts and William Murfitt's wife was then taken from the room as William Murfitt had died.

William Murfitt's wife said that both she had William Murfitt had taken a dose of salts from the same tin at breakfast time on the previous morning. She said that although they had tasted funny, and had felt unwell after taking them, that her husband had not complained of any ill effects and she said that she did not like to attribute her indisposition on that day to the salts.

She added that she thought that she had purchased the tin of salts used on that morning a few days earlier, which the police report stated would probably have been on 30 April 1938.

It was reported that William Murfitt’s wife had initially disclaimed all knowledge of having purchased any cyanide or other poison whatsoever, or of having ever signed the Poisons Register, and had also said that she was unaware of her husband having done so either. However, she did say that she recalled that something had been bought the previous summer for the purpose of destroying wasp nests but said that she didn't know what it was. However, it was later pointed out to her that she had bought some cyanide from the chemists where she bought the salts from on 7 September 1937 and had signed the Poisons Register for it. However, she said that she had no recollection of that and said that if she had done so then it would have been for William Murfitt. The police report noted that in point of fact, William Murfitt had purchased a 1 oz. bottle of cyanide from the regular chemists on 4 September 1937 and had then made a further purchase of a 4oz. bottle of cyanide on 8 September 1937, in both cases signing the Poisons Register.

William Murfitt's wife said that as far as she was concerned, her purchase of the bottle of cyanide had been accompanied by that of a tin of Enos Fruit Salts and that both items had been debited to William Murfitt's account, and subsequently paid for by him by cheque.

She also said that she was unaware that William Murfitt had had any poison, but said that she thought that if he did, that he would have kept it in a locked wine cupboard for which only he had a key.

She also added that William Murfitt had interested himself in photography but said that all of his developing had been done at Leesons or Boots. It was noted that cyanide of potassium was used in photography for intensifying.

It was noted that the only other people in the house were the secretary who had been with them for nine years, the maid that had been with them for seven years and the cook who had been with them for six years, all of whom were described by William Murfitt's wife as being most trustworthy and with whose work she was satisfied. She said that neither she nor her husband had ever had occasion to remonstrate with them and said that she didn't consider that any of them had tampered with the salts.

It was said that there was no suggestion that the tin of salts had been interfered with prior to breakfast time on Monday 16 May 1938. It was also noted that the reverend had called round at 10.30am on 16 May 1938 to see William Murfitt's wife and had stayed for not more than 15 minutes. William Murfitt's wife had then gone out at 10.45am on 16 May 1938 alone in her car to see her sister in Wisbech. She said that she had spoken to William Murfitt at breakfast time about contemplating the visit and said that it was at that time that she decided to go. She added that William Murfitt had tried to dissuade her from making the journey as she was not feeling very well, and it was not a nice day.

William Murfitt's wife said that she had left William Murfitt at the farm and didn't see him again until she returned later that evening and said that when she did, she found out for the first time that he had been out for the day to his farm in Ickburgh.

William Murfitt's wife said that she frequently went to see her sister under such circumstances and said that the route she took, took her past Hall Farm which was situated close to Quays Farm and which was occupied by the Hall Farm Farmer and his housekeeper, whom it was concluded in the police report was the main suspect in the case, and that as she passed she would have been in view of the house.

William Murfitt's wife said that on the day in question, 16 May 1938, she thought that she had seen the Hall Farm farmer as she drove past, and that he might have seen her too. She said that both the farmer and his housekeeper at Hall Farm would have known that she was going to Wisbech if they had seen her driving by their house, and said that in fact, on one occasion she had actually stopped and told the Hall Farm farmer where she was going when she stopped to speak to him on one of the occasions that she had previously made the trip.

William Murfitt's wife said that she later left Wisbech at about 5.15pm and returned home at about 7pm and said that shortly after she saw William Murfitt drive in with another man who then drove away almost immediately without entering the house. She said that after William Murfitt entered the house he took his gun and went out to do some pigeon shooting and returned at about 8pm.

William Murfitt's wife said they then had supper together and that she then retired to bed between 9.15pm and 9.30pm leaving William Murfitt in the dining room reading a newspaper. She said that he followed her to bed about a quarter of an hour later but made no reference to getting up early the following morning which she said was not unusual.

When William Murfitt's wife was asked who would have known about their practice of taking salts each morning, William Murfitt's wife said that all the residents of the house would have known, as well as their good friends from a nearby farm that dined with then frequently, and also the farmer at Hall Farm and his housekeeper.

When William Murfitt's wife was asked about the habits of the maids she said that they would get up at 7am each morning and that it was always the first maid’s practice to take cups of tea to their bedrooms as well as to the secretaries room. She also added that all meals in the house were prepared by the maids. She said that it was the first maid’s responsibility to lock up each night but said that she herself would lock the front door on occasions when she arrived later or there were visitors. However, she said that that position did not arise on Monday 16 May 1938 as the only known visitor had been the reverend. She said that when she went to bed she had left the maids in the kitchen and said that they should have locked up but said that she could not actually say who did so, nor could she say whether the secretary was in bed then, or whether she was still out. She noted that one of the rear doors was sometimes left open if the secretary was out late.

The police report noted that there had been four keys to the front door, although only three could be accounted for. It was noted that according to William Murfitt's wife and all the other members of the household, that there had only been three keys to the front door. One was kept by William Murfitt, another by his wife and the third by the son that was at sea. William Murfitt's wife had kept hers in her bag, and William Murfitt had kept his on his chain ring, and the third was found in the son's bedroom after the murder.

However, the police said that they discovered the existence of the fourth key when they made enquiries at the local locksmiths to ascertain whether any unauthorised person had obtained a duplicate key. It was said that the enquiry proved negative, but that it was revealed that on 29 December 1936, that the firm of Messrs. Andrew & Plumpton Ltd in Bury St Edmunds had supplied William Murfitt with two keys, which had been invoiced from Messrs Archibald Kenrick & Sons Ltd and which were paid for through William Murfitt's account. It was also noted that whilst those two keys had been on order, that the lock itself had been removed and a temporary one fitted.

The police report noted that when they had drawn William Murfitt's wife attention to that, that she at once recollected the incident. She then explained that when William Murfitt had taken over Quays Farm that there had been two keys to the front door and that both she and William Murfitt had one each. She said that when William Murfitt then had the two new keys cut that William Murfitt had given one to their son.

William Murfitt's wife said that in about January 1938, William Murfitt had taken her key away from her in order to attach a disc to it, and gave it back to her about a fortnight later, but said that it was not until the matter was raised with her that she said that she realised that William Murfitt had given her one of the new keys and not her original key. It was reported that she had since searched for her old key but had failed to find it.

As such, the police report noted that there had in fact been four keys to the front door and that one was missing and could not be accounted for since about three weeks before William Murfitt's murder. The police report noted that it was difficult to speculate what had happened to it.

It was noted that William Murfitt's wife had stated that the only employees authorised to enter the house were the garage man whose job was to change the wireless battery and the gardener whose job it was to bring in coal and vegetables into the house.

The police report noted that William Murfitt's wife reluctantly stated, at first, that since her early married life William Murfitt had had affairs with various women, and that he had been intimate with the farmer’s wife at Moseley Farm. It stated that it appeared that the other farmers wife would frequently dine alone with William Murfitt and his wife and that William Murfitt would accompany her home alone and take advantage of the position to seduce her. William Murfitt's wife stated that she became aware of that situation about two years earlier and that it had resulted in quarrels between them. She added that she had threatened to obtain a divorce in order that William Murfitt could, if he chose, go away with the farmer’s wife. However, it was heard that William Murfitt had pleaded forgiveness from his wife and that she had eventually agreed to stay, on a promise that there would be no repetition of such conduct, and the whole affair later seemed to have been forgotten and the relationship between William Murfitt's wife and the farmer’s wife was re-established. It was also noted that William Murfitt appeared to have been indifferent as to the continuance of the friendship and had told his wife that she could please herself.

It was further noted that the farmer at Moseley Farm had no knowledge of the incident and that it wasn't until Sunday 22 May 1938 that his wife enlightened him, after deciding in light of the police enquiries which would have brought the matter to his attention to confess the affair to him.

It was also noted that during the time that William Murfitt had been intimate with the farmer’s wife that she had become pregnant and had gone to London to consult a well know abortionist and subsequently had a miscarriage. It was further noted that the London abortionist was later brought before the courts and sentenced to 12 months imprisonment and that a newspaper cutting dealing with the case was found in William Murfitt's private documents.

It was further noted that on Sunday 15 May 1938, William Murfitt and his wife and the farmer from Moseley Farm and his wife both spent the day together on William Murfitt's motor yacht at Horning on the Norfolk Broads and that there had appeared to have been a complete atmosphere of friendliness. The police report noted that William Murfitt's wife was empathic that nothing improper had taken place between her husband and the farmer’s wife for the last two years and the police report stated that there was no evidence to the contrary but did state that it did seem that the period was considerably less than that.

It was noted that when the Moseley Farm farmer and his wife visited Quays Farm that they would invariably come by car, driving into the yard at the back of the house and by entering by one of the rear doors.

It was heard that about 18 months before the murder that William Murfitt and his wife became friendly with the farmer at Hall Farm and his housekeeper and had continued to be friendly with them until about February 1938 when William Murfitt had suspected that the housekeeper had been cheating when they played cards together. It was also said that there had been some local scandal concerning bets the housekeeper had placed on a horse with a bookmaker in the names of local residents, including the Moseley Farm farmers wife that William Murfitt had had the affair with.

It was stated that it was in consequence of those disclosures that the Hall Farm housekeeper went to Scotland on 9 March 1938, although she had said that she had done so for the purpose of visiting her dying father which was later proven to be untrue. The Hall Farm farmer stayed at his farm and continued to visit William Murfitt, and William Murfitt later said to him, 'Now your housekeeper has gone away, I shouldn't think you would have her back. I know she is only your housekeeper'. However, it seemed that the Hall Farm farmer had resented that and had said, 'Whatever she had done I shall stick to her. She has been very good to me'.

It was also heard that in December 1937 that William Murfitt's wife had visited Hall Farm and that the housekeeper had taken her upstairs and shewed her a valuable mink coat that she said she had to sell for a friend from Scotland. William Murfitt's wife said that she asked the Hall Farm housekeeper why she didn't keep it for herself and said that she had told her that she wanted something lighter in weight. William Murfitt's wife said that the housekeeper later told her that she had bought the coat and wanted to sell it. William Murfitt's wife said that she suggested that she should see her own furrier, Messrs Ralli Ltd of Regent Street, who might buy it, and said that the house keeper shortly afterwards told her that she had sold the coat to Messrs Ralli Ltd for £150.

William Murfitt's wife said that she told the wife of the Moseley Farm farmer about the fur coat and of the transaction and said that the Moseley Farm farmers wife knew that a similar coat had been stolen from a lady in Newmarket, a friend of hers, and that as a consequence, the Moseley Farm farmer's wife informed the local police.

The police report noted that on or about 27 September 1937, a valuable mink coat was stolen from Somerville Lodge on Fordham Road in Newmarket from a woman and that the police later recovered the coat from Messrs Ralli in London and criminal proceedings against the Hall Farm housekeeper were being made.

It was heard that whilst the housekeeper was in Scotland the Hill Top farmer borrowed a car from William Murfitt and drove part of the way to see her. He returned on 19 April 1938 and returned the car and asked William Murfitt's wife if she would visit his housekeeper, but William Murfitt's wife said that her husband had told her that his housekeeper was to have no friends in Risby. Whilst the housekeeper was in Scotland, the Hall Farm farmer went to see William Murfitt's wife and said, 'We are in a bit of trouble about a coat which the housekeeper bought on a racecourse when she was with your husband'. William Murfitt's wife replied, saying, Did Bill know she bought the coat on the racecourse?' and said that the Hall Farm farmer replied, 'No. A lady and her daughter with a Daimler car, who had had a bad day at the races sold it to her. She bought the coat and put it in the back of your husband's car and covered it over with a rug and didn't tell Bill'.

William Murfitt's wife said that she knew that William Murfitt had been to Newmarket Races with the housekeeper, but said that the chauffeur, had driven her back after dropping William Murfitt off in Newmarket. During conversation between William Murfitt's wife and the Hall Farm farmer, William Murfitt came into the room and his wife repeated to him what the Hall Farm farmer had said to her in front of him and then told the Hall Farm farmer that his housekeeper had shewn her a mink coat that she had told her that she had for sale for a friend in Scotland and that she had afterwards bought it. She said that the Hall Farm farmer then replied, 'I know, but perhaps she didn't want to say she had bought it at Newmarket. But you will not be brought into it'. William Murfitt's wife said that she had at the time not been interviewed by the police but said that she knew that the police were making enquiries about a fur coat that had been stolen from a woman, and told the Hall Farm farmer that if she was questioned about the matter that she would speak the truth, but said that the Hall Farm farmer said, 'You won't be brought into it'.

It was noted that two or three days later, on 20 April 1938, William Murfitt's wife and William Murfitt were interviewed over the fur coat by the police and William Murfitt's wife was shewn a mink coat but had been unable to say definitely that it was the one that the house keeper had originally shewn her but said that it was like it.

The following day or two after the interview, William Murfitt's wife said that she saw the Hall Farm farmer in a nearby lane and said that she said to him, 'I have been brought into this coat business. I have told them all I know. I am sorry if I am doing you any harm, but I can only speak the truth'. She said that the Hall Farm farmer then said, 'She put the coat at Newmarket in the back of the car', but William Murfitt's wife said, 'She couldn't have done that, because my husband always locked his car'. She said that the farmer then said, 'Bill wouldn't remember if he locked his car or not'.

It was heard that William Murfitt's wife didn't see the Hall Farm farmer again until the day after the murder when he came across to her house and sympathised with her in her bereavement, and said to her, 'I’ve been through a similar thing, when my wife died. You know, Bill always said he would go off like a puff of wind'. William Murfitt's wife said that the Hall Farm farmer then tapped her on the shoulder and said, 'Remember, we never let our friends down', which she said she regarded rather significantly.

William Murfitt's wife said that she didn't see the Hall Farm house keeper again after 1 or 2 March 1938, before she had gone to Scotland, but said that she understood that the housekeeper had called at her house after William Murfitt died and had delivered a cake made from ingredients that she had provided her a long time previously.

It was heard that during the time that the Hall Farm farmer and his housekeeper visited Quays Farm that they would sometimes enter by the front door but sometimes by the back door. It was heard that when they first started coming round they would ring the bell, but later would just tap quietly at the door instead.

It was heard that William Murfitt's wife said that she had found the Hall Farm housekeeper in the upper rooms of her house several times in somewhat suspicious circumstances. She said that one of them was when she had been resting on her bed and had heard a tap on her door and said that the house keeper had just walked into her room uninvited and said, 'Sorry, I rang the bell and couldn't make the maids hear. I've got a car outside and wondered if you would like to come up town with me'. William Murfitt's wife said that the house keeper had got into her house unnoticed but said that although she had regarded her behaviour as strange, she had not attached any great importance to it.

On a second occasion, William Murfitt's wife said that the house keeper had been to Quays Farm for supper and had made an excuse to go to the bathroom. She said that the house keeper was a long time and so she went to see where she was and said that she found her in her bedroom, standing very quietly against a wardrobe. She said that the housekeeper told her that she had rung the bathroom bell for one of the maids to render her some personal service and was waiting for her. However, William Murfitt's wife said that the bell had just been recharged and so the maids would have heard if she had rung as she had said.

It was said that the only time that William Murfitt's wife had had a theft in her house had been the year earlier, during the period that the Hall Farm farmer and his house keeper had been frequent visitors, when William Murfitt's wife noticed that some sheets were missing, but William Murfitt's wife said that she had been unable to say who had taken them.

It was also heard that the housekeeper from Hall Farm had given William Murfitt's wife to understand that her father was a retired barrister and that her husband had been a doctor in India and had died on the polo field. She had also told her that her husband had entertained the Prince of Wales and that she herself had been presented at Court. She had also told her that she had known Jack Buchanan, a famous theatre actor, as she had been brought up with him as a child as he had lived on an estate next to her father. She had also told her that she had a lot of money invested in a bank in London but that she had no need to touch it, and that she had a bungalow let to two doctors in India.

William Murfitt's wife said that on one occasion she went to see her sister in Wisbech and was accompanied by the Hall Farm farmer and his housekeeper and said that whilst there the house keeper had made an excuse to leave the table when at dinner and had gone to the bathroom. However, she said that the housekeeper was a long time and that when she went to see where she was, she found her in her sister's bedroom near a wardrobe. She said that the housekeeper told her that she had had a ladder in her stocking had had been looking for a needle and cotton to mend it. William Murfitt's wife said that her sister lost a nightdress from the house but could not say how it went, but it was noted that it had been one that had been shewn to the housekeeper.

William Murfitt's wife said that on another occasion when the parties had been at her sister's house, her sister had missed £5 from her handbag that had been in the dining-room in which the housekeeper had been at one point left alone.

William Murfitt's wife said that she had at no time suspected that William Murfitt had had any improper relations with the housekeeper, and the police report stated that during the course of the investigation, there was no evidence that there had been any improper relations.

When the police questioned William Murfitt's wife more closely regarding William Murfitt's love affairs she noted that he had been intimate with the young daughter of a gamekeeper, but that their association had ended some years before and the girl was noted to be married to a wealthy man in Essex.

It was also suggested that William Murfitt had been unduly familiar with his young married niece although William Murfitt's wife denied that. It was heard that he had bought her some riding clothes but William Murfitt's wife said that she was satisfied that he had done so because the niece had no father.

In the police report it was also stated that it was suggested that the son had gone to sea because of a difference with William Murfitt, but William Murfitt's wife denied that although she did note that it had been William Murfitt's intention to take on a certain man as a farm manager, but it was said that they would have lived locally and the son would always be able to return.

William Murfitt's wife said that William Murfitt had no enemies and that none of his employees held any grievance against him, although she did note one exception, that being a shepherd that William Murfitt had dismissed shortly before he was murdered and whom against William Murfitt had taken steps to eject from a cottage on the farm. She also said that William Murfitt had quarrelled with a gamekeeper employed on the estate and that William Murfitt had approached his employer with a view to getting him removed but said that she was not conversant with the reason. His wife also said that William Murfitt had allowed a man to park his car at Heath Barn Farm but said that after William Murfitt had been told of the large amount of whisky the man had drunk at a pub, he had then refused him permission to continue parking his car there.

William Murfitt's wife said that despite William Murfitt's infidelity, they lived happily together.

When William Murfitt's wife was questioned by the police as to why after William Murfitt's murder and knowing that there had been interference with the tin of salts, had she continued to use all other foods without examination, William Murfitt's wife had said that it had never occurred to her.

When the police searched the farm, they found several diaries belonging to both William Murfitt and his wife. In William Murfitt's wife’s 1937 diary they found references to William Murfitt's association with the farmer’s wife at Moseley Farm and when questioned, William Murfitt's wife said that she had written the entries for William Murfitt to read and said that she had deliberately left the diary out so that he would see it. In the diary she had mentioned that he was being watched and mentioned speaking to a solicitor about a divorce, even though she had not done so, although she said that she had gone to see her solicitor in order to alter her will so that her sons got her estate, and not some other woman.

When the secretary was questioned she said that she had lived at the farm almost as a member of the family and confirmed William Murfitt's wife statement regarding the general routine. She said that she had had her cup of tea at 7am on the Tuesday 17 May 1938 and said that she had remained in her room until 8am and had then gone down for breakfast, taking down with her her empty cup and then got her porridge from the cook and went into the dining room, noting that William Murfitt's wife was already in there, appearing to have just come in. The secretary said that William Murfitt's wife then poured out a cup of tea for her as usual and said that after eating her porridge she had returned to the kitchen to get some bacon and eggs for herself and some porridge for William Murfitt's wife. She said that whilst she was eating her bacon and eggs, William Murfitt's wife got up from the dining table and removed a tin of Fynnon Salts from the top of the sideboard and immediately took the lid off the tin and remarked, 'These salts look funny. They are brown'. She said that William Murfitt's wife then shewed her the salts and said that they were lightish brown in colour.

The secretary said that she then saw William Murfitt's wife take a teaspoon and remove the brownish particles from the tin and place them in a slop basin on the table. She said that William Murfitt's wife remained standing and said that she saw her then take some of the salts from the tin and put them into a tumbler and mix them with some hot water from a water jug, and then place them on the dining-room table where William Murfitt usually sat. She said that William Murfitt's wife then observed, 'They look cloudy'.

The secretary said that William Murfitt then came into the room about five minutes later and said 'Good morning', and sat at the table reading his newspaper. The secretary said that William Murfitt then picked up the tumbler of salts and was about to take them when William Murfitt's wife told him that there and been some brown stuff on them but said that she didn't remember her exact words. She said that William Murfitt didn't say anything, and then drank the salts.

The secretary said that after William Murfitt had drunk the salts he said, 'Are you sure these are salts? They taste very funny', and said that his wife replied, 'Yes, of course they are. Shall I take them back to Leeson's?' The secretary said that William Murfitt's wife then produced the tin and drew the paper packet of salts out of the tin. She said that William Murfitt then looked at them and said, 'They are damp. You can see the tin is nasty. You can't do that'. She said that William Murfitt's wife then said, 'I'll have them dried in the oven', and forthwith took them into the kitchen. She said that when William Murfitt's wife returned into the kitchen, William Murfitt was red in the face and got up from the table and went over to the other side of the table and fell on it, holding his head on his arms. She said that William Murfitt's wife then said, 'Get a doctor', and the secretary said that she then telephoned for the doctor.

The secretary said that two men from the garage then went to help William Murfitt and that she went to the gate to wait for the doctor and said that when she went in with him William Murfitt was dead.

The secretary said that William Murfitt's wife told her soon after that the salts she had taken on the previous morning had given her diarrhoea very badly and that she had had to pull up in her car on the way to Wisbech to see her sister.

The secretary said that the only poison that she knew of in the house was some arsenic that she had purchased on behalf of William Murfitt in February 1938.

The secretary said that the previous day, 16 May 1938, William Murfitt's wife had left the house between 11.30am and 12 noon for her sisters and that William Murfitt had gone off to visit his farm in Didlington, in Norfolk. She said that she didn't see either of them again by the time that she left the house at 5.20pm and said that she returned to the house at 11pm, coming in by the side door which had been left unbolted, and after locking it up, she went to bed. She said that she had been brought home by her fiance who had left her at the gate and who had not come in to the house.

The secretary confirmed that the relationship between William Murfitt and his wife with the Hall Farm farmer and his house keeper had finished about 2 1/2 months before the murder due to the housekeeper having used William Murfitt's wife's name in a betting transaction and having cheated at cards. She also confirmed that William Murfitt's wife had told her that the housekeeper had shewn her a mink coat, as well as telling her about finding the housekeeper in her bedroom and said that she advised her to lock her drawer.

The secretary also said that on one occasion the housekeeper had come into the house unnoticed and had tapped on the door to her bedroom, however, she noted that the friendship was such that the housekeeper could walk into the house whenever she liked.

The first maid said that she got up at 6.30am on 17 May 1938 after William Murfitt had shouted asking if she was getting up. She said that William Murfitt had evidently got up early that morning, which she said was not unusual, and had been out and had returned to the house. She said that when she went downstairs she first went to unlock the front door but discovered that it was already unlocked, but shut, which she said she didn't regard as unusual as William Murfitt sometimes unlocked the front door to see if men were waiting at the farm gates. She said that she then unlocked the side door and that when she went to unlock the back door, she found that it was already unlocked, evidently by William Murfitt, who she said was then in his office outside.

She said that the rest of the morning was pretty much as William Murfitt's wife and the secretary had described, as did the cook, who was the second maid.

The cook said that she had helped the first maid to clean the dining room and said that the maid had swept it with a hoover and that she had removed certain articles from the sideboard and then after dusting, had replaced them, noting that she had remembered the tin of Fynnon Salts standing rather forward on the right side of the sideboard. She noted that William Murfitt and his wife had started to take Fynnon Salts some weeks earlier and that since then the tin had always been left standing on the sideboard, usually on the left side. She said that she remembered that prior to that they had taken Kruschen Salts that had been kept in their bedroom. She said that she had thought that it was strange to have found the tin of salts on the opposite side of the dressing table that morning.

The cook said that after the doctor was ordered, William Murfitt's wife asked her and the maid to clear the table quickly before the doctor arrived and said that she helped to remove the utensils and wash them, noting that it had been her that had washed the slop bowl.

Both of the maids said that they had seen a woman in the drive on 12 May 1938, and the cook said that she thought that the woman had been the Hall Farm housekeeper.

The police report stated that they made efforts to trace where William Murfitt had been during the last 24 hours before his death. They said that they knew that on the Sunday 15 May 1938 that he had his wife had been out with the farmer from Moseley Farm and his wife, whom William Murfitt had previously had an affair with, at Horning on the Norfolk Broads.

It was heard that the following day, Monday 16 May 1938, that the foreman at the Ickburgh Farm which was sometimes referred to as the Didlington Farm, had called William Murfitt at 6.45am and asked him to send a horse over to the farm, but said that William Murfitt had replied, telling him that he was coming over himself.

It was said that it was known from the maids that William Murfitt had left Quays Farm between 11.30am and 12 noon that day and that at 3pm he was seen at the farm in Ickburgh by the foreman there who said that he talked to him about work on the farm.

It was said that William Murfitt had remained on the farm for about ten minutes but assumed that he had no doubt spent some time looking around the farm. He later, on the same afternoon went to visit a gun dog trainer at Mundford in Norfolk and took a dog away with him that the gun dog trainer had trained for him. It was said that William Murfitt had left the gun dog trainer at 4.45pm, stating that he was going home to tea, which was noted as being a distance, between Mundford and Quays Farm, of about 14 or 15 miles.

It was said that the maid saw William Murfitt return home at 5.30pm at which time he was also seen by a shepherd employed at Hall Farm.

A personal friend of William Murfitt then called at 5.45pm and they went into the dining room to discuss business which they finished at about 7pm when they both left the dining room and then drove around the farm until 7.30pm and then returned to the house at which time the friend left.

It was noted that there was some differences between the times that William Murfitt was said to have finally returned to the house, with his wife and the maids saying that it was about 8pm whilst a game keeper from Hyde Wood Lodge in Risby said that he had spoken to William Murfitt outside his cottage, about a quarter of a mile away from Quays Farm, at 9pm, saying that he then drove away in his car. The game keeper said that he was positive about the time as he said that he met William Murfitt's kennel man shortly after and that that had been at about 9.30pm, noting that he had invited the kennel man into his cottage but that the kennel man had declined on account of it getting on.

It was said that the following morning, 17 May 1938, the first person to have seen William Murfitt was the kennel man who lived in a bungalow on the farm and a horseman who both say that they saw him at 6am drive out of the farm in his car. He was then seen at 6.10am travelling in the direction of Heath Barn Farm by a horseman and another farm worker. He was then seen at 6.20am by a builder’s labourer who was on his way to work who said that he had seen William Murfitt carrying a gun and standing by his motor-car on a field of peas alongside the Bury to Newmarket Road.

He was then seen driving along New Risby Road towards the farm by two farm workers at 6.30am and then again by the horse-man that had seen him earlier.

It was said that it had already been determined that William Murfitt had called the maids at 6.30am and then had two cups of tea in his office soon afterwards.

The postman said that he called at the back of the house at 6.45am and delivered the mail to William Murfitt personally.

At about the same time, the foreman at Ickburgh said that William Murfitt telephoned him to say that he was sending over a drilling machine.

William Murfitt was then seen by the foreman at Quays farm at about 6.50am who said that he saw him in his office in his yard. He said that they conversed about getting some potatoes ready for market and said that William Murfitt told him to send a lorry to the Didlington farm with some manure and implements. He said that William Murfitt seemed quite normal and his usual self. It was noted that it was during that conversation that the maid brought out the tea for William Murfitt.

It was stated that it was known that the cook had seen William Murfitt at 7.40am and that the farm foreman then saw him again at about 8.15am in the farm-yard where they walked together to the back door of the house. The foreman said that he asked William Murfitt about some directions for moving some sheep and said that William Murfitt told him, 'Leave it till later on and I'll see you again', and that he then went into the house. The Forman said that he then returned to the house at 9am and was told that William Murfitt was very ill and was on the sofa. He said that when he then saw the other farmer in the hall he was told that it was 'too late’ and said that he then went in to the dining room and saw William Murfitt was dead.

The foreman said that it was William Murfitt's usual practice in the mornings to come out of the side door at the rear of the house and that he had never seen him come out by the front door.

The foreman said that when he arrived at the farm on that morning he had met two men from Hall Farm who were waiting for him for a tumbril which he had previously said he would lend them.

The foreman said that he would often go into the house for instructions and had also been in the dining room at breakfast time on previous occasions. He said that he knew that William Murfitt frequently took salts in the morning, saying that he used to see them on the tray when it was taken to his bedroom, but noted that that had been before the previous Christmas and said that he had never seen salts taken in the dining room and that neither did he know that that a tin of Fynnon Salts was kept in the dining room.

The police said that they closely questioned the farm foreman regarding the imminent introduction of the new farm manager into the business and the effect that that would have on his position as foreman and the foreman said that he was quite all right with it saying that he thought that it would lighten things for him and noted that he knew the man and had been a pupil under him before and described him as the type of man that he could get along with.

When the police investigated the use of the cyanide the previous summer they determined that the gardener was the only man that had used it. He told the police that there had been some wasps nests on the farm and that he had asked William Murfitt for some stuff to do away with them and said that about two days later William Murfitt had given him a small bottle of cyanide. He said that he kept the bottle until he had got rid of all the wasps and then buried it, but couldn't remember where. He said that he had given the cyanide to no one else and whilst he had had it he had kept it in a locked shed for which only he had a key. He said that he was positive that William Murfitt had only given him one bottle and when shown a 1oz. bottle, said that that had been about the size of the bottle that William Murfitt had given him.

When the police interviewed the shepherd from Quays Farm that had been dismissed he said that William Murfitt had been annoyed when he had found that he had been away from his flock. He said that his notice had terminated on 26 April 1938 and asserted that he had not seen William Murfitt or been anywhere near the farm house since then. He said that during his time at the farm he had been into the farm house twice, each time into the kitchen for sheep medicine. It was noted that although he had regarded his dismissal as unfair, he had not appeared to hold any real grievance against William Murfitt.

When the police interviewed the gamekeeper that William Murfitt had complained about the gamekeeper said that he had seen William Murfitt shoot a pheasant in a wood at Heath Farm and said that he had no right to shoot game over his farms and had a few words with him over it and reported him to the owner. The gamekeeper said that William Murfitt afterwards reported him to the estate office three times, but said that in spite of that, he never had any grievance against William Murfitt. He said that he had been working on the Rearing fields from 5pm on 16 May 1938 through to 7.30-8am the following morning.

When the police interviewed the man that had been parking his car at William Murfitt's farm, he said that he bore no grudge against William Murfitt. He lived in a cottage within 100 yards of Quays Farm. He also said that he had never been in the farm before either. He also said that he had never purchased or been in possession of any poison and would not know what cyanide of potassium was like. The police noted that he was a man prone to petty thieving.

When the police spoke to the farmer at Moseley Farm whose wife William Murfitt had been intimate with he said that he had known William Murfitt for several years before he took over Quay Farm in 1931. He said that he knew that William Murfitt had been fond of other women but said that he didn't know that he had been unduly familiar with his wife and said that they had never quarrelled as they had never had a reason to. He said that he never left his own farm on 16 May 1938 and didn't go there on 17 May 1938 until after he had heard of William Murfitt's death. He also said that he had not purchased any cyanide for 10 or 11 years and had none in his possession.

When the police interviewed the wife of the farmer at Moseley Farm she confirmed many of the things previously mentioned, including the fur coat affair, and said that she had been in London on 16 May 1938 which they confirmed with a gentleman who said that he had accompanied her there, leaving her address at 8.30am and going to London and making purchases at Burberry's and then returning to Fornham at 7.30pm. The police looked into the trip to London and said that they were able to confirm that the Moseley Farm farmer's wife had been to Burberry's as well as a number of other shops across the day.

When the police went to see the farmer at Hall Farm they said that he was reluctant to make any statements at first without his solicitor being present but eventually made a statement without recourse to the presence of a legal adviser. He had resided at Hall Farm since 1926 and had initially said that he had known his housekeeper since before his wife died in 1926. He was born in Calcutta in India and was about 60 years of age and was described as an educated and intelligent man. When he initially spoke about his housekeeper he initially said that he would stand by her and had said that he had seen a barrister friend in London and said that he intended to instruct a leader to defend her, and also added that if she was sent to prison for the theft of the fur coat that he would stand by her and would always provide her with a home. He said that he understood that there was a possible motive in his housekeeper wanting William Murfitt or his wife dead in that it would destroy evidence against her regarding the theft of the fur coat, but he said that William Murfitt's wife's evidence was of little importance to him and that he would be able to repudiate it from the witness box.

He said that he drove his housekeeper to Grantham on 9 March 1938 from where she went on to Buckhaven and then to Scotland to visit relatives. He said that he later went to see his housekeeper in Scotland on 2 April 1938, saying that the younger of William Murfitt's sons drove him as far as Newcastle where he was inquiring about getting a job on a boat, and returned on 5 April 1938 when the son picked him up for his return journey.

He said that on 15 April 1938 he borrowed William Murfitt's car, as he had smashed his own, and went to Peterborough and then left the car there and went to Buckhaven the following day. He said that when he got there, his housekeeper told him that the local police had been to interrogate her about the loss of a mink coat, and the Hall Farm farmer said that that was the first that he had heard of the matter. He said that when he spoke to the local police on 18 April 1938, they told him that they didn't think that his housekeeper should have anything to do with William Murfitt and his wife while the investigation was pending. The farmer said that he and his housekeeper returned to Hall Farm on 19 April 1938 and that he returned the car to William Murfitt that evening. The farmer added that the sole reason he and his housekeeper stopped going to Quays Farm was because the police had advised them not to. He averred that from the time that he had returned the car to William Murfitt, to the time of William Murfitt's death, he had not entered Quay Farm or been in its yard.

When he was asked to account for his movements on 16 May 1938 he said that he had been on his farm all day dressing a field for mustard seed and said that in the afternoon he had not been away from his house for more than half an hour. He said that the following day, 17 May 1938, he had got up at 8am and did not go out before breakfast. He added that his housekeeper was not away from the house all day on 16 May 1938 and said that on 17 May 1938 she had not got up until lunchtime.

He admitted to having purchased some cyanide from Boots the chemists in Bury St Edmunds around September 1937 saying that he had needed it to destroy some wasps and hornets and said then, that after three days, he destroyed the bottle by putting it in a slow combustion stove noting that he didn't give any to anyone.

The Hall Farm farmer said that although he had taken meals at Quay Farm, he never saw any salts there and didn't know that William Murfitt or his wife took them.

During the police interview, the police noted that they felt that the Hall Farm farmer had not been altogether open and frank, noting that he had been careful to confine his movements of himself and his housekeeper to his farm and grounds on the material days and to account conclusively for the disposal of any cyanide that he had had.

When the police interviewed the housekeeper, they said that she said that she had been a house keeper for the farmer for about ten years and remembered when William Murfitt took over Quay Farm about five years earlier. She said that she had met William Murfitt's wife for the first time at the Rectory about 18 months earlier and said that they had accepted an invitation to a tea party at Quays Farm and that following that they had become quite friendly and had frequently called at the farm for supper and to play cards. She confirmed that she had gone to Scotland on 9 March 1938 and said that she was told not to communicate with William Murfitt or his wife, in her own interest, by the police when they interviewed her, and that she returned to Hall Farm on 19 April 1938.

She said that after that she didn't go to Quay Farm until the day after the murder.

She added that she was aware that William Murfitt was a diabetic but said that she was unaware that he or his wife took salts.

She said that there had been no differences with William Murfitt or his wife, but the reason they stopped going to Quay Farm was because the police had advised her not to.

When the police interviewed the Hall Farm farmer and the housekeeper, they both inferred that they knew a great secret that would probably explain his death but said that they could not repeat it as it would be a breach of confidence.

A policeman said that he took the Hall Farm farmer to one side and encouraged him to tell him the secret, but said that he would not, although he said that he gathered from the farmers manner that he was hinting that William Murfitt had committed suicide. Similarly, another officer took the housekeeper to one side and said that when he pressed her for the secret, she told him that the truth of it was that William Murfitt had taken his own life.

When the police questioned a maid at Hall Farm she said that the housekeeper had told her that her husband was a doctor abroad and that her brother was studying to be a doctor and that her grandfather was the Earl Marshal of Scotland. She said that she had also told her that she had attended the Coronation in London the year before and said that on his death, her father would come into the title. She also said that the housekeeper had told her that she had been educated at college and presented at Court and had shewn her a photograph of herself in Court dress which was usually kept on the mantelpiece in the drawing room.

The maid at Hall Farm said that the housekeeper had gone off to Scotland in the summer for about six weeks and said that whilst she was there, she had written and asked her to forward a bottle that she would find in the left-hand corner of the bench in the cloakroom. The maid said that the housekeeper did not say what was in the bottle but said that she had thought that it had been some kind of medicine. She said that when she got the bottle she found that it was a green bottle that had the label 'Poison' and 'Cyanide of Potassium', on it. She said that the bottle was in the corner near the bench, but not in it and said that it was the only bottle in the cloakroom and that when she had shewed the letter to the milk boy she had said, 'She surely would not want that', and said that the milk boy had agreed with her and so she had written back to say that she couldn't find it and didn't send the bottle. The maid added that in reply she received a postcard from the house keeper that read, 'Thank you. I have written Master regarding same. He will attend to it. I hope you are managing alright. Kind Regards'. The police said that they tried to locate the letter that the maid had received but could not find it but said that they did find the postcard and noted that it was kept for evidence.

When the housekeeper for Hall Farm later returned, the maid said that she told her that the green bottle with the word poison and cyanide of potassium on it had been the bottle that she had wanted her to send her, saying that she had wanted it to destroy some wasp nests in Scotland, as the poison was difficult to get there.

The police said that they then spoke to a horseman that had been at the farm for 12 years but had since left who said that in the early summer of 1936 he had been stung by a hornet on the farm and said that he knew that the farmer had some cyanide of potassium and said that together they destroyed the nest. He again said that in July 1937 there had been a wasp nest in the cornfield near Heath Barn and that after speaking to the farmer, he had given him a bottle of cyanide of potassium to use and added that in August there were two more wasp nests on Hall Hill and that he had used the same cyanide to destroy them. The description of the bottle was similar to the one given by the maid who had been asked to send the bottle on to the housekeeper in Scotland.

The police said that they again spoke to the farmer at Hall Farm but said that he repeated that he was certain that no other person could have had access to the bottle that he had had and said that his housekeeper could not have had access to it either. The police noted that it was evident that the farmer, if the statements of the maid and the horseman were accepted as being true, must have been lying, but said that the farmer was definite in his assertions and could not be shaken.

When the police questioned the Hall Farm housekeeper again she told them that although she knew what cyanide of potassium was like, she had never purchased any, possessed any, or used any, and said that she would not know how to use it to destroy a wasp nest. She also said that she was certain that there had never been a bottle of cyanide in the house as it had always been locked away in a safe.

When the police asked the housekeeper to account for her movements on 16 May 1938 again, the day before William Murfitt died, she said that she had got up before lunchtime and then after that read the newspaper. She said that she then spent the afternoon and evening hemming some serviettes and that after supper she went out onto the lawn an watched the farmer cut the lawn. She said then, that after talking together with the farmer until about 9.45pm they went into the house and both retired to bed at about 10pm. She said that she didn't get up again the next day until about 10.45pm when she said that the Hall Farm farmer then told her that William Murfitt had had a stroke.

When the police asked the housekeeper why she had taken the cake to Quays Farm on the day after William Murfitt died, she said that William Murfitt's wife had given her some ingredients to make a cake before she went to Scotland on 9 March 1938 and said that it wasn't until she had made a cake for herself that she had remembered the ingredients and said that she then made them up, but said that whilst she had intended to take the cake over on 16 May 1938, she had forgotten and had left it in the pantry until she remembered it on 18 May 1938. She said that when she had taken it over on 18 May 1938, she had not asked for William Murfitt's wife to give it to her, but for her sister, if she was there.

She added that she had been friendly with William Murfitt and his wife for about two years and said that she had frequently taken supper and dinner there, but never breakfast or lunch and said that whilst she knew that they had a sideboard in the dining room with some bottle standing on it, she didn’t know what they contained and had never seen any salts there.

The housekeeper said that she was sufficiently familiar this William Murfitt and his wife to enter their house when she liked, but said that she would always ring the bell and said that if she got no answer that she would call out. She said that she would never enter without somebody’s permission and on a few occasions when she had run the bell and got no answer she would walk into the hall, but would never go upstairs without being told to do so. She said that on one occasion she had gone upstairs and had seen William Murfitt's wife lying down on a bed. She said that they sometimes used the front door, but very often used the back door.

The police noted that there were a number of discrepancies about what the housekeeper had said regarding the cake. They said that the maids at Quay Farm had said that the housekeeper had asked to see William Murfitt's wife. They also said that she had seemed rather nervous which was odd as she was usually calm and collected. They also said that the cake looked fresh.

Further, the maid that replaced the other maid at Hall Farm when the house keeper was in Scotland said that William Murfitt's wife had given the housekeeper some fruit to make a cake in March and said that it was not a success and the cake was burned. The new maid then said that on the Friday before William Murfitt's died, the housekeeper had made two cakes and on the Thursday after William Murfitt's died, she looked in the cupboard and saw that one of the cakes was missing and said that when she asked about it, the housekeeper told her that she had taken one over to William Murfitt's wife as she owed her one. The police report noted that from the probability that the housekeeper had taken over one of her own cakes, the consideration of why the housekeeper should have wanted an excuse to visit Quays Farm the day after William Murfitt's murder, gave rise.

The police said that they also questioned the new maid about the movements of the housekeeper on 16 and 17 May and said that she corroborated when the housekeeper had told them, adding that she had never seen any cyanide of potassium and didn't know what it looked like. The police report noted the parrot like fashion of her answers which recited the housekeeper’s movements and asked her if she had been promoted on what to say by the housekeeper, but the maid said that she had not. The police said that they then questioned the maid with regards to what she or the housekeeper had done on other irrelevant and more recent dates but said that the maid was unable to respond. The police said that they asked the maid why she was able to so clearly recollect the activities of the housekeeper and the farmer on 16 May 1938 and yet entirely forget the events of more recent days, and said that she said that she had just remembered. The police report noted that the reason for that was a matter for conjecture.

The police further noted that when they further interviewed the Hall Farm farmer and the housekeeper they didn't tell them what the maid and the horseman had told them and said that after taking a statement from the farmer they gave him and the housekeeper the opportunity of conferring in anticipation that the housekeeper would then corroborate him in his lying statement, and noted that as anticipated, she more or less did so.

The police report noted that it appeared inexplicable why the farmer and the housekeeper should lie in connection with their possession of cyanide if it had no connection with the death of William Murfitt, and stated that it was quite evident that, for some reason, there was some form of collusion existing between them.

The police report noted that when they asked the housekeeper about the note that she had sent the maid regarding the green bottle in the cloakroom, she had become most confused and after hesitating for a bit eventually agreed that she had done so, and when asked what the bottle had contained, she had said that it had contained lotion. The housekeeper then spoke to her solicitor in private and then agreed to make a statement on the matter and said that the bottle had contained boracic crystals, which were noted as being very similar in appearance to cyanide and said that she had asked the maid to send them to her.

The police report noted that boracic crystals could be purchased in any chemist’s shop in small white packets at threepence for four ounces and stated that it seemed absurd that the housekeeper had wanted the maid to send them to her thorough the post when she could have so easily purchased them in Scotland or elsewhere.

The police said that when they later interviewed the Hall Farm farmer again in the presence of a man that said he had used cyanide to kill wasps at the farm, the farmer admitted that he had made purchases of cyanide from Boots the chemist in Bury St Edmunds on 23 August 1934, 7 November 1936, 30 September 1936 and 19 July 1937. He said that he then remembered giving cyanide to his old foreman but said that he had put it away safe afterwards. He also remembered giving cyanide to other farm workers over that period.

When the farmer was asked if the housekeeper had asked him to send her some cyanide whilst he was in Scotland he said that he did remember the housekeeper asking him to send her something, but could not remember if it was a bottle. He added that he could not recollect the house keeper asking him to send her any cyanide and said that he did not send her any as far as he could remember.

The police report noted that throughout the interview with the farmer he had obviously been in a condition of considerable mental distress and that in his endeavours to be ultra-careful in what he said he had frequently had recourse to saying that he could not remember. They stated that he was very nervous and laid back on an old armchair with his eyes closed and his head thrown back, and was in an almost prostrate condition.