Age: n/a

Sex: male

Date: 2 Sep 1958

Place: Kelvin Gardens, Southall, Middlesex

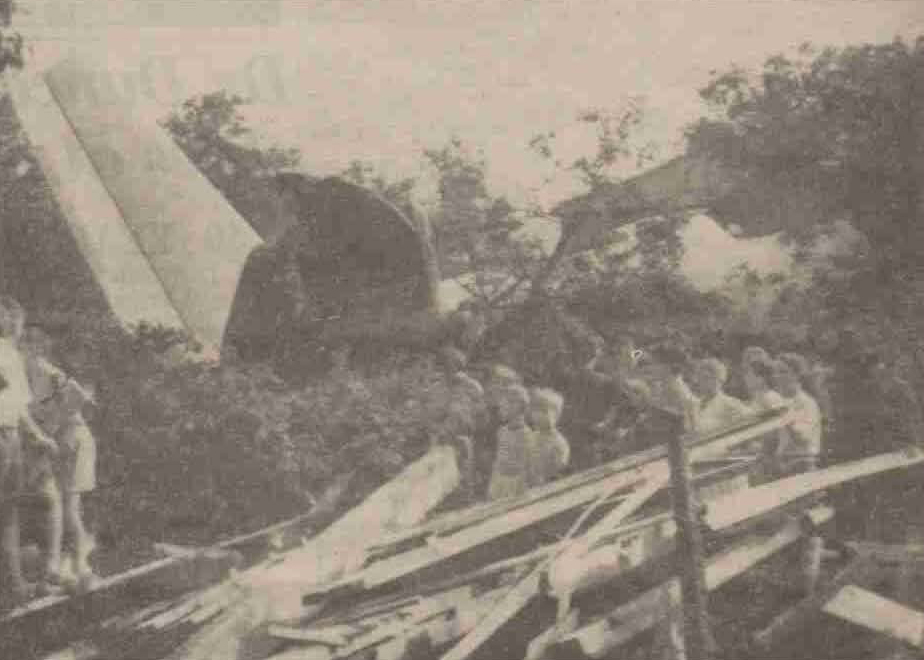

A Vickers VC1 Viking, a twin engine freighter plane, crashed into some houses in Kelvin Gardens, Southall on 2 September 1958, killing seven people.

An open verdict was returned at the inquest after it was heard that disturbing facts had been revealed during the investigation showing that there was no doubt that breaches of regulations had been made.

Three members of the plane crew died in the crash as well as a woman, two children and a 3-week-old baby that had been in the houses that the plane crashed into. Eight other people were also injured or had to be treated for shock.

The dead were:

Peter Major was said to have had over a million miles flying time and had been with Independent Air Travel for three years. He had been a bomber pilot during the war.

The Britannia Vickers VC1 Viking aircraft, registration G-AIJE, had just taken off from London Airport bound for Tel Aviv in Israel via Nice, Brindisi and Athens, but it crashed minutes after take-off following engine problems.

The aircraft had been overloaded with two Bristol Proteus turboprop engines as cargo and it was heard that recent maintenance had been carried out by unqualified engineers. It was also heard that the pilot had been tired and had not received adequate training for an event in which engine power was lost.

The aircraft had taken off at 5.54am but within a few minutes the flight crew reported engine problems and requested a return to Blackbushe Airport which was cleared by Air Traffic Control. They then descended to 3,000 feet but were unable to maintain that altitude and continued to descend.

The aircraft sent out a Mayday call at 6.32am and shortly after crashed into Kelvin Gardens and burst into flames. The crash destroyed two houses, No. 6 and 7, and severely damaged two others.

It was said that there had been a heavy mist as the plane had skimmed low over the house tops and then hurtled into the houses in Kelvin Gardens.

A man that lived in Kelvin Gardens and saw the plane crash from his front door said, 'I went to the front door to get the milk. The plane was so low I saw the pilot. There were no engines running. The plane took a lamp-post right out, and missed my front wall by a couple of inches. It took the fence. I just shut the front door and grabbed my three children and ran out'.

It was reported that witnesses said that they saw one of the crew waving outside of the aircraft just before the aircraft crashed. It was said that as it came down that it was already on fire and that when it crashed into the houses it exploded.

A woman that had lived in Alandale Avenue said, 'I was just going to work when I saw the plane. It looked as though the pilot was trying to avoid the houses and reach some nearby playing fields. Soon after it crashed I heard some terrible screams'.

The explosion was heard by a number of people, one of whom was a 39-year-old painter who had been in Dormers Avenue who then rushed round to see what had happened. He said that when he got to Kelvin Gardens that he saw a 14-year-old boy at the first floor window of Elizabeth Gibbins's house which was on fire. He said, 'The boy climbed out on the sill and got ready to jump. There was a little group of us below and we held our breath as he hesitated a minute and then went inside again. He came back to the window with his little nephew in his arms. I shall never forget the scene as long as I live. The boy dropped his nephew into the arms of another man who was waiting below, then jumped and I caught him'.

The boy and his nephew were then sent to the burns unit of Mount Vernon Hospital in Northwood, Middlesex where they were treated, their conditions initially being described as 'fair'.

Other victims of the incident were:

The man that had been in the bed was rescued by an ex-detective that had lived in Dormers Avenue. He said, 'I jumped over my back garden fence to get to the crash and was amazed to find the man still in bed. Two others joined me and we pulled him into a garden. Seconds later the place was an inferno'.

A 41-year-old man that had helped the painter catch the children said, 'It was like a battlefield, but we managed to get five children out of the wreckage. Some of them had jumped from upstairs windows. All were badly burned. I never want to see anything like this again. The older Mrs Gibbons and the baby were dead. The boy was going round in a daze looking for his mother. There were flames and smoke blinding and choking us'.

Later during the recovery operation the WVS brought a mobile canteen to the scene and balanced their urn on a kitchen chair brought from a neighbour’s house.

Fifteen appliances from surrounding fire stations and 60 firemen were called to Kelvin Gardens to put out the fire which took them two hours.

The aircraft engines were found in the front gardens of No. 6 and 7 Kelvin Gardens.

A report into the crash stated that the probable cause was that 'the aircraft was allowed to lose height and flying speed with the result that the pilot was no longer able to exercise asymmetric control'.

It was not known what the exact reason was for the aircraft losing power and then losing height and speed, but a public enquiry found several issues, including:

The day after the crash, several theories for it were put forward:

At about the same time the Socialist Member of Parliament for Southall wrote to the Minister of Transport and Civil Aviation and asked for an enquiry to be held into the build-up of aircraft for London and adjacent airports before the accident, signals received from the aircraft, whether it was thoroughly air-worthy and whether its cargo of turbo-jet engines was properly secured.

On Tuesday 16 December 1958 it was reported that Scotland Yard had sent the Coroner a letter regarding the crash, but it was not clear what it said.

An inquest was held which was adjourned multiple times and concluded on Thursday 29 January 1959 in which an open verdict was returned.

The inquest included an hour-long playback of messages exchanged between the plane, London Air Traffic Control and Blackbushe Airport, which was also listened to by the captains widow.

In the first message the Captain was heard to say, 'I have engine trouble and I wish to return to Blackbushe'.

The last message was a 'May Day, which ended with, 'We are going into'.

The Captain's first message was at 6.09am on 2 September 1958. At 6.20am he informed Blackbushe that he was flying on one engine but would be starting the other for landing.

Other messages concerned his height and course, as a result of which London Airport was warned and a crash crew alerted and all out-bound traffic stopped. This was then followed by the May Day.

The inquest heard that Captain Peter Maygor was the only experienced member of crew on the plane and that with an inexperienced first officer and an inexperienced engineer that he was essentially on his own.

The Coroner asked the chief air traffic control officer with the Ministry of Transport and Civil Aviation a number of questions on the matter and when he asked him whether it was true that the captain was the only experienced member of the crew he replied, 'I would not like to express an opinion'. When the Coroner then asked him, 'Mayger an experienced pilot, was trying to get the plane down with an engine he could not unfeather, with an inexperienced radio officer?', the chief air traffic control officer said, 'I would agree that if they were inexperienced the burden must fall on Mayger'.

The Coroner then noted that the radar cover assistance for the plane appeared to have been unsatisfactory, stating that 'The plane was miles out of its course'.

When he again questioned the chief air traffic control officer about the extent of the captains experience, the captains wife interviewed and said that neither she nor the Airline Pilots Association wished to blame anybody. However, the Coroner said, 'I am here to find out the truth. The jury is not bound to accept my interpretation of the facts'.

The Chief Investigating Officer at the inquest said that he had found something in the wreckage of the plane that could have bearing on the cause of the plane crashing, saying, 'something I would go no further than to say might be a factor, an electrical failure of the starboard feathering pump motor'.

A man that had previously been employed by Independent Air Travel and who used to be a wartime Pathfinder said that he had resigned from the company but that when he had worked there that he had come across 'plenty' of instances of pilots becoming sleepy. He said that he resigned 'because I found the work difficult and rather dangerous. On one occasion when I went to Israel I was extremely tired. Numerous factors made the whole operation a little trying'.

The inquest further heard that after he resigned from Independent Air Travel that he continued to fly for them on a freelance capacity. When he was asked, 'Why did you go on doing it after you left their service? Were you willing to kill yourself for a few pounds?', the man said, ''On reflection it looks as though that is the case'.

When the man was asked whether he had volunteered to give evidence at the inquest because he disliked Independent Air Travel, the man replied, 'No Sir'.

When he was cross-examined about his statement that he had said that he had found his employment dangerous, he was asked, 'Did you know that Independent Air Travel have never during the whole course of operations had a crash except this one?', the man said, 'yes, I have heard that'.

When he was questioned about an earlier statement that he had made in which he said that whilst on a trip as a freelance pilot the plane's Captain had gone to sleep, he explained that before the Captain went to sleep that the plane was put into automatic pilot. When he was asked, 'With you in possession of the controls? Is it a perfectly proper operation to fly on the automatic pilot?' the man said, 'Yes, under proper supervision'. When it was put to him, 'But you were a pilot?' the man replied, 'I did not have it on my licence to fly the plane'.

When the man was asked whether he had told Independent Air Travel that he was not properly qualified to fly that plane, a DC4, he said, 'I did not tell them but they knew'.

He also admitted during questioning to have struck a Ministry of Transport and Civil Aviation examiner in 1952 after he failed him in an instrument flying test. However, it was noted that in fairness to him he did pass the exam a month later with another examiner.

Another pilot that gave evidence and who had been detailed to investigate the crash said that he thought that the aircraft had been overweight by about 700lb when it had taken off and said that most off the figures given by captains were inaccurate or at the very least subject to guesswork. After giving his evidence the Coroner said, 'I think you have made some serious allegations today. You are suggesting that every company gives inaccurate figures to pilots. I think you are making some wild statements'.

It was also noted that while the pilot was giving evidence that the Coroner had said to him, 'I want you to stop being aggressive and answer my questions. I don't like your manner'. He said that he found that the aircraft had been 700lb overweight when it had taken of, noting that the amount of petrol used to wash down one engine, running the engines and taxiing would have halved the overweight suggested by the Ministry of Civil Aviation. He then said, in answer to a question, 'I think most figures given to captains are inaccurate, or at the very least are subject to a very great deal of guesswork'.

When the operations officer for the Ministry of Civil Aviation commented on the other pilots evidence, he said, 'I disagree with everything he said'.

When an Operations Officer with the Ministry of Transport and Civil Aviation gave evidence he said that on 26 August 1958 when he looked at certain flying-time records of Independent Air Travel that he found apparent infringements of an order on flying-time limitations, stating that there appeared to be considerable breaches of the regulations by the company in relation to several pilots.

When the Coroner remarked, 'I am here to enquire into the conduct of the company', the QC for the company intervened and said, 'You are here to enquire into the deaths of these seven individuals'. The Coroner then responded, 'They may be associated'. The QC then said, 'It is quite wrong for you to make that assumption'.

Other evidence was heard at the inquest regarding the aircraft having been overloaded. The Superintendent with the CID headquarters at London Airport said that the aircraft was appreciably overloaded when it took off. He said that during his investigations with a load sheet that had been put in by Captain Mayger and from an examination of the material salvaged from the wreckage, which he said amounted to about 950lbs which was not accounted for in the log, he found that there was no reflection between the two.

When a representative for Independent Air Travel gave evidence he stated that after doing some calculations that he found that the Viking aircraft had been overloaded by 950lb, plus excess petrol that was not shown in the loading sheet.

However, another witness at the inquest from the Civil Aviation Ministry said that he did not think that the Viking aircraft had been overloaded enough to cause danger. He said that he found that the aircraft had been 700lb over the maximum permissible weight and that any excess must be nibbling at safety margins.

When he was questioned, 'He said, 'Clearly there was a dangerous situation at some stage, but there must have been some other more significant factor than excess weight'.

A marshalling supervisor at London Airport said that he had gone to the aircraft whilst it was nearly finished being loaded and overheard some telephone conversation. He said, 'I heard the engineer telephone Blackbushe. He said he was worried, and the way he was putting it over was that he was telling them off at the other end very angrily'. He said that after the telephone conversation he asked the engineer if everything was fixed and said that the engineer replied, 'No, we will not be out to-night or tomorrow morning'.

However, the marshalling supervisor said that he later heard the aircraft engines being run quietly and said that the aircraft then left at about 6am.

The engineer that had been detailed by Independent Air Travel to go from Blackbushe to London Airport to supervise the loading of the aircraft agreed that he was not a licensed engineer. When the Coroner said, 'Alterations were made to units and gaskets, and that aircraft should not have taken off without the certificate of a licensed engineer. You could not have given that certificate?' the engineer replied, 'No, sir'.

He said that the aircraft had taken off from Blackbushe Airport in Hampshire and had landed at London Airport to be loaded with engines after which it was to depart for Israel. He said that he had been a passenger on the plane from Blackbushe Airport to London Airport and that when they arrived they found an oil leak in one of the constant speed units which eh said must have developed between Blackbushe and London. He said that they had to wait for the engine to cool down before they could deal with it.

At that stage in the inquest, a constant speed unit similar to the one that had been in the Viking aircraft was carried in and placed on the Coroner's table and the engineer demonstrated how the defect was remedied.

At the subsequent inquiry, it was said that the engine had been 'taken to bits and put back together' without the required tests and certification by an authorised person.

The Superintendent with the CID headquarters at London Airport said that he had been informed that an engine fault had developed at London Airport on 1 September 1958 and that he had determined that the defect was not supervised by a licenced engineer holding an Air Registration Board certificate.

He then noted that he found that Gerald Altena, the aircraft's First Officer had little experience, stating, 'From my information on that aspect of it, he had little or no training to take the position of First Officer on this flight'.

When the operations officer with the Civil Aviation Ministry commented on Gerald Altena's qualifications, he reiterated that opinion, saying, 'From my information he had little or no training to take the position of first officer on this flight'.

After hearing the evidence the Coroner adjourned the inquest and said, 'No one is accused, and there is no one on trial, and there is no case to present. This is an enquiry into the deaths of certain individuals. I want to make that clear'.

When the inquest concluded on Friday 30 January 1959 the jury returned a unanimous open verdict.

After the verdict was returned, the defence for Independent Air Travel said, 'During the hearing and your summing up you made a number of assumptions and accusations against Independent Air Travel, my clients, which are not supported by a shred of evidence. I am therefore desired to state publicly that my clients strenuously disputed all the charges you have seen fit to level against them and if the verdict of the jury had been other than it was they would, on advice, have applied to the High Court to set it aside. They will now look forward to the day when an impartial tribunal will investigate, at a proper public enquiry, the causes of this unfortunate accident'.

The Coroner then asked the defence, 'Are your clients suggesting that this has not been impartial?'.

The defence then said, 'I am not making any suggestion at all'.

The Coroner then said, 'You made a suggestion that is equal to, or more serious than, the one I made'.

The defence then said, 'You quoted Pontius Pilate at an early stage in these proceedings and I will also quote him'. He then quoted, in Latin, 'What I have written, I have written'. After a few moments of silence the Coroner then said, ''And await a reply'.

The defence then shrugged his shoulders and said, 'Never mind. My conscience is clear. This was quite an impartial enquiry. I could have said a lot more'.

When the Coroner had summed up he had said that certain disturbing facts had been disclosed. He said, 'For example, there is no doubt that there have been breaches of regulations, breaches of air navigation orders and air navigation regulations. In my opinion these breaches do point to negligence, but I do not at the moment feel that they reveal any evidence of culpable negligence which concerns you or myself. There has obviously been a considerable amount of laxity in the conduct of this company. I would feel myself that pilots, including the managing director, would appear to be having a considerable licence. I am under the impression, I may be wrong, that there appears to be a certain laxity in discipline. I would hope that that laxity does not exist in other commercial air companies, otherwise it would be a sad reflection on British aviation'.

When the Coroner finished his summing up, he said, 'I personally, and you are not bound to accept my views, feel that an accident verdict is not enough. I do not think that there is sufficient evidence to justify a verdict of manslaughter against some person or persons. Whether you think there is enough evidence to return an open verdict is a matter for you to decide'.

A public enquiry was later held in March 1959.

At the public enquiry other evidence came to light, including the fact that a radio engineer had certified a check of the Viking's radio by another man without actually inspecting the work.

It was also heard that the Captain had been 'hopelessly wrong about where he was'. It was said that the Captain had been losing height and had been unable to restart the starboard engine propeller which he had stopped.

The inquiry report stated that Independent Air Travel, which had since appointed new directors, had deliberately disregarded regulations by overworking the pilot and the crew and overloading the plane.

However, it was heard that as the six-month time limit for prosecutions had expired, that it was impossible to bring proceedings.

When the inquiry referred to the flying hours and duty hours worked at Independent Air Travel the QC that was holding the inquiry said, 'This matter had come to the notice of the Ministry of Transport and Civil Aviation. It is not a matter which had been overlooked. In fact, it had reached the stage where it was under consideration when this accident occurred'.

On 6 July 1958 it was reported that the report into the crash stated, 'With a company so organised and with such an attitude to it's responsibilities it is perhaps only surprising that an accident such as this did not occur before'.

The report also stated, 'Since this accident the company has taken great pains and spent a good deal of money in putting it's affairs in order, with the result that it's organisation now bears favourable comparison with that of other larger companies, and so that , if it is given a chance to do so, it is now able to provide a safe and proper service'.

It was further noted that the managing directors that had been in place at the time of the crash no longer had any interest in the company.

The report also stated that the pilot ought not to have taken off in the aircraft, knowing that it was overloaded, and with a crew which he must have known was not of proved competence, and at a time when he himself was suffering from fatigue. However, the report added, 'The conduct of the pilot and the whole course of the events, in my opinion were contributed to by the deliberate policy of the company, which was to keep its aircraft in the air and gainfully employed regardless of the regulations or of the elementary requirements which should join for the conditions of working of it's employees, or the maintenance of an aircraft'.

The report also stated, 'I concur in the submission of Council for the Air Registration Board that with a company so organised and with such an attitude to its responsibilities it is perhaps only surprising that an accident such as this did not occur before. In my judgement any responsibility of Captain Mayger is to be viewed in the light of his position as an employee upon whose shoulders an intolerable burden was placed.

The managing director of Independent Air Travel at the time of the crash, a 40-year-old Polish man, later wrote a letter to the Ministry of Transport and Civil Aviation, saying, 'I feel the allegations against myself are completely unjustified'.

On 16 July 1959 there was a heated clash in the House of Commons when the Labour Minister of Transport and Civil Aviation denied that his department had been negligent over the enforcement of the air safety regulations.

The clash was reported as beginning when the Labour Minister of Transport and Civil Aviation announced that he proposed to bring in legislation to tighten-up the air transport licensing regulations. However, it was reported that he maintained however, that 'high standards' were set in the present inspection system. However, he was asked how he could 'square up' his comments about inspection with the happenings in the Viking disaster by another Labour MP who said, 'Don't you think it is a reflection on your Department that this kind of murder by private enterprise has got to take place before you are goaded into action'?

However, the Labour Minister of Transport and Civil Aviation was said to have retorted that the Labour MP should not let his dislike of private enterprise colour his judgement and said that Independent Air Travel had been prosecuted in the past by the Ministry and that another prosecution had been pending when the accident had occurred.

Another Labour MP said that the country was shocked at the apparent lack of control over the air transport companies, and then went on amid Labour cheers to say, 'Negligence of the Ministry in not taking action before was a contributory factor in bringing about this tragedy'.

However, the Labour Minister of Transport and Civil Aviation described that as 'nonsense', maintaining that air firms were already inspected to a high standard.

Several other Viking Freighter aircraft also crashed around the same time.

On 1 May 1957 a Viking aircraft crashed two minutes after leaving Blackbushe bound for Libya with troops. 34 people died in the incident.

On Monday 7 September 1959 a Viking freighter that had been flying ballet scenery and costumes from Athens to the Edinburgh Festival for Performance crashed into the sea off of Corsica and sank.

On Friday 17 October 1958 it was reported that a twin engined Viking freighter aircraft that had left London Airport at 10am had crashed in Belgium.

see www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk

see Wikipedia

see YouTube

see Birmingham Daily Post - Friday 30 January 1959

see Daily Mirror - Friday 28 November 1958

see Western Mail - Friday 30 January 1959

see Daily Mirror - Friday 20 March 1959

see Liverpool Echo - Monday 06 July 1959

see Daily Mirror - Thursday 16 July 1959

see Birmingham Daily Post - Tuesday 27 January 1959

see Belfast Telegraph - Wednesday 26 November 1958

see Daily Mirror - Monday 07 September 1959

see Torbay Express and South Devon Echo - Friday 17 October 1958

see Daily Mirror - Wednesday 17 December 1958

see Liverpool Echo - Tuesday 16 December 1958

see Birmingham Daily Post - Tuesday 16 December 1958

see Daily Mirror - Tuesday 17 March 1959

see Birmingham Daily Post - Friday 28 November 1958

see Coventry Evening Telegraph - Tuesday 02 September 1958

see Daily Mirror - Monday 07 September 1959

see Unsolved 1958